Dancing in a Circle

Every year in late November there’s a débutante ball held in downtown Baltimore. It’s called the Bachelors’ Cotillion, an old patrician ritual of introducing young girls into high society. The “coming-out” party is one of the oldest of its kind in the country. On this night, the daughters of the elite are presented to eligible old men. For the opening dance, fathers take their offspring arm-in-arm in a slow trot around the perimeter of the dance floor displaying their daughters to the satisfaction of their own kind—their rich friends, their squash buddies—like showing prize horses at an auction. The onlookers clap in adulation. There’s drool on many a cummerbund. The circuit is now complete—the incestuous revolution of the elite.[i]

Baltimore has an aristocracy in every sense of the term. It’s not for nothing that affluent whites call it “Smalltimore,” a place where family names still matter, where the private school you went to carries just as much currency as anything else. Where everyone knows everyone else. The Bachelors’ Cotillion is the apotheosis of this. On the night of her coming out, the parents of each “deb” usually throw an elaborate dinner party for family friends. Red meat and champagne, a round of toasts. Often there is an after party as well. Yet one of ball’s main expenses is flowers, costing upward of several thousand: each girl receives enough bouquets to fill a gutted horse carcass. Because every young woman needs a room full of rotting hyacinths.

People sometimes forget that Baltimore is below the Mason-Dixon line, and that it still retains much of the Old South.[ii] The city had slave jails until July 24, 1863—a few months after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Today, over 150 years later, the same structures of racism are still in place, evolved, adapted, but still producing fundamentally similar results. They have become part of Baltimore’s “culture,” of institutions like the Bachelors’ Cotillion.[iii] And it’s not like this has been dying out. The débutante ball has seen a resurgence in recent years, one component in a general revival of all things aristocratic. But the nature of the aristocracy has also evolved. While traditionally the event had been barred to all but the oldest and most-established families in Baltimore, it is now open to anyone with the money to pay dues (ie, to non-WASPs). In 2015 more than ever, the upper class seems to want—to need—to place as many flowers as possible between them and all those below.

The rebirth of this tradition in the years following the recession speaks to how crisis is managed in Baltimore today. Economically the city is still “recovering,” as they say: its unemployment rate, at 8.4%, remains higher than it’s been since the 1990s. The resurrection of slave-era institutions and attendant cultural signifiers provides a means of dealing with this—by creating buffer zones between the wealthy and a “dangerous” population whose very existence exceeds the needs of the economy. This division always occurs along lines of race—in fact constantly creating and re-creating race as we think of it. In order to manage a rise in surplus labor, when human bodies exceed in absolute terms the number of jobs (productive or otherwise) that can be afforded for them, certain bodies are forcefully removed from the workforce altogether, either through incarceration, austerity, or death. In Baltimore, for the entirety of its history, a racial circuit has existed wherein black bodies—those who have been cast out—secure the existence of “labor” and “civil society,” which are constituted via their distinction from the unfree, whether slave, “underclass” or criminal. All the while the aristocracy keeps on dancing, trying to forget that its halls, its homes, its diamond rings were all forged in the flames of its own lower hells.

Off to the Races

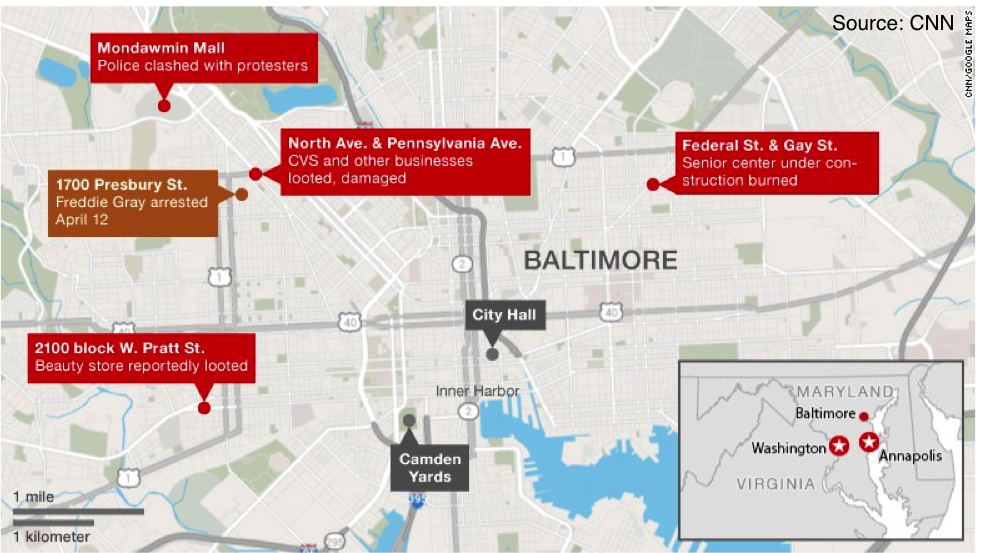

Recent riots in Baltimore over the death of Freddie Gray have been the largest there since those following the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968. They began on April 25, 2015, when a group of protestors split off from a peaceful rally and began hurling bottles at cops and smashing patrol cars.[iv] This happened not far from Camden Yards[v] where white Orioles and Red Sox fans remained untouched behind stadium gates. Others, drunk and racist, brawled with protestors outside nearby sports bars. But Baltimore’s true elites were far from downtown. That Saturday was the 119th running of the Maryland Hunt Cup, a steeplechase horse race in Reisterstown, Baltimore County. A steeplechase, for those less schooled in equestrian pastimes, is where the horses jump over a bunch of fences and ditches and try not to fall over. In Maryland, this particular race provides rich people with an excuse to break out their finest, brightest spring clothes. Bowties, salmon-colored shorts, Lilly Pulitzer dresses in red and green. Flowery sunhats. Mint juleps and Natty Boh beer. White Baltimore ascends toward its ideal form. Down in the fields a horse trips and falls, snapping its leg and pitching the jockey off into the mud. It will be soon be dragged out of view of the garishly-clad onlookers to be shot.

Against what progressives are saying today and what they have been saying for years, Baltimore is not a tale of two cities. It’s a tale of one city in which one group exploits the living fuck out of another. Of one city where white real-estate investors are able to eat crab cakes and watch horses jump up and down in circles not in spite of but because of the displacement of black families from their homes in East and West Baltimore. Like the horse track, it’s a circle that just connects to itself in the end. And in Baltimore, like in every US city, the arc of this brutal circuit can be traced without interruption back to slavery and its often unacknowledged counterpart: the birth of the American industrial empire. Sometimes this gets talked about, in school or during an episode of The Wire. But rarely is it as visceral as during a riot. Rich white bros can choose to turn The Wire on and off, to engage with it politically or aesthetically. But the riot has no stop button. At its most effective it is something that demands attention, that demands decision.

We Are All Fucked

If Baltimore were two cities, I’m from the one on top. But it’s really just a single circuit of exploitation, and I just happened to be born higher up on its lighter, richer rungs, though not at all the highest. The neighborhood I’m from—Roland Park—is just north of downtown. After college I moved to Upper Fells Point[vi]—a gentrified neighborhood just south of East Baltimore—which was my home until 2013. Growing up, I attended one of the many private, all-male, predominantly white schools to the north of Baltimore.[vii] We prided ourselves on “diversity” and spent a lot of time discussing honor, character building, and lacrosse. When we went downtown it was to go to Camden Yards, the National Aquarium, the Inner Harbor—the institutions that police and the National Guard were so keen to protect during the riots. Other times we would wander into the “ghetto” to buy liquor underage, reveling in how dangerous, how hood—and later how Wire-esque—the slums seemed. It was gracious, the progressives among us thought, for private schools to offer scholarships to kids in these parts. Like a king pardoning his subjects, we were doing our bit.

By all means, my social position in Baltimore has always been on the side of the exploiters.[viii] Roland Park is in the richest zip code in Baltimore City (by median household income) but it pales in comparison to the clusters of wealth in Baltimore County. In any other generation I probably would have gotten a decent-paying job and shut up. Indeed, many of my better-positioned high-school classmates have done just this. At least 30% of my class is now in Finance, Business Consulting, Marketing, or Real Estate. This 30% has managed, for now, to claw out some marginal foothold in a middle class that is simultaneously shrinking and ascending, until soon the “middle” can be dropped entirely. But the fact is that I was born into a fucked generation—Generation Zero—the poorest since those who came of age during the Great Depression. It’s no secret that the recession had the greatest and most lasting impact on “millennials.” In 2012, 36% of young adults (ages 18 to 31) were living with their parents. As of March 2015 the unemployment for 16- to 24-year-olds remains at 13.8%, which is more than twice the 5.6% rate for the nation as a whole. Student debt has more than doubled since the recession, now at roughly $1.3 trillion. For the Class of 2013, nearly 70% of students graduated with student loan debt, with average debt per borrower of $28,400. All in all, our generation ranks lower on every measure than previous generations have at the same age—especially in those crucial years of entry into the labor market.

Of course this all looks much worse for black youth, and for them it hasn’t meant just unemployment but being systematically rounded up and sent to mass prisons. Even though blacks make up only 13.2% of the US population they account for one million of the 2.3 million[ix] Americans incarcerated today.[x] This occurs along lines of gender as well. Black men are six times more likely than white men to be incarcerated,[xi] and they receive sentences 10% longer than whites who committed the same crimes. So high is the rate of imprisonment that roughly one in every three black males born today can expect to serve jail time at some point in his life.[xii] Not great odds.

But the point is that very, very few in our age group—both black and white—have truly escaped the crisis. Our situation has had the effect of pushing us all to the growing realization that the system as it exists is as fucked as we are. While this has always been the case, in the last few years it has become undeniable. And there’s nothing to turn back to, nothing to salvage. Every attempt to save capitalism—Keynesianism, the New Deal, neoliberalism, whatever—has ended in complete failure, at best deferring the crisis to our moment. And instead of salvation, our moment is now generating people such as myself. People who, despite their own origins, have discovered a far greater affinity with hooded looters than with the “middle class” (or whatever other lie) they were supposed to belong to.

In Baltimore, the connection is salient: so far the largest day of riots was ignited by members of Generation Zero. Around 3pm on April 27th a group of high-school kids in northwest Baltimore, in the Mondawmin area, responded to a social-media message calling for a #purge. They began hurling rocks, bottles, and bricks at cops in riot gear. Whatever they could find.

The media latched on to these events, becoming obsessed with the idea of “juveniles” doing crazy things. This image, quoted from the New York Times, caught fire: “Hundreds of young people gathered outside a mall in northwestern Baltimore and confronted the police, throwing rocks and bottles at officers.” What also went viral was the video of a mother beating her son for participating in the riots. For some, she became a patron saint of reason. For others her actions were unwarranted. The point is that the idea of the “juvenile” became problematic, something that demanded discussion and resolution. On the 27th, cops, older black clergy and civil rights leaders all banded together to call on the “juveniles” to come home. David Simon, the creator of The Wire, was adamant about this: “Turn around. Go home. Please,” he begged. Even Ray Lewis got involved.

But that night, as a senior center burned in East Baltimore, it became clear that the “juveniles” could never really go home. Because their futures had already been ransacked. And the fact is that you’re fucked too, you just might not know it yet. Being born into a screwed generation comes with a set of consequences. One is the decision, which everyone must make, between maintenance and destruction.

Last Resorts in the City of Firsts

As second grader around time of the city’s bicentennial in 1997, I remember people making a big deal of one of Baltimore’s official nicknames, “America’s City of Firsts.” What I wasn’t told was that many these “firsts” where hardly things to be bragged about. My own neighborhood at the time was a pristine example: Designed in part by Olmsted, Jr., Roland Park is considered the first planned suburban community in North America. It also happens to be one of the first neighborhoods in the country to legally bar blacks. This was made possible under Baltimore’s 1910 racial zoning ordinance, itself another first, as the earliest redlining law in the US.[xiii] Roland Park is also, debatably, home to the world’s first planned shopping center, built in 1896. It’s not without irony that a white, wealthy enclave should produce the model for what was to become a major target in the Baltimore riots—Mondawmin Mall.

Placed in this context, looting is never a “senseless act of violence.” When protestors torched the CVS in Sandtown-Winchester, they were confronting—and exposing—historical structures of inequality. When asked if he would rather have his neighborhood burned, one protestor countered, “My neighborhood is not burned right now. What you’re getting an example of is what’s really inside of everybody. For about twenty years—I’m forty-one—I have witnessed atrocities that build up and build up.” These atrocities are those of the global system of production that Baltimore is embedded in, which is based ultimately on the continuous dispossession of masses of people in order to extract work from them, even while they are barred from the benefits of their labor. In Baltimore this process takes on an unambiguously racial character. There are historical reasons for this.

In the eighteenth century, with the rise of its tobacco economy Maryland became a major plantation colony and developed an increasing thirst for slaves. With labor needs declining in the Chesapeake area, slavery peaked in Maryland around 1810 when the state held 111,502 slaves, a little under 10% of the country’s total slave population. But Maryland, and especially Baltimore, continued to play a significant role in the slave trade. Between 1815 and 1860 Baltimore’s port became one of the most popular disembarkation points for ships carrying slaves to New Orleans and other southern ports. As a result, the slave trade was a significant industry in the city, as dealers had slaves interned in private jails before selling them for a profit to plantation owners in the Deep South. In 1838 one such jail on Pratt street was selling “likely fellows, aged 13 to 23” for $500 to $650. That’s about $10,000 to $14,000 when adjusted for inflation.

The last of Baltimore’s slave jails closed its doors in 1863, but they never really went away. Black bodies are still locked up in droves, but today their numbers are tallied by a different kind of monetary calculus. Rather than being sold for a profit, every year Baltimore-City inmates cost the state over $37,000 per person—despite private prisons and prison factories, the prison system in the US has largely transformed into a massive sink for surplus capital and surplus bodies, helping to stave off the dual pressures that arise in the economy’s continually-building crisis. But the end result is the same: the prison, like the slave trade, produces a mass of cheap, surplus bodies, deprived even of the basic exploitation offered by the wage. In short, it produces race. Through the shackling of black bodies, the debris of capitalism’s inherent crises are hidden—literally locked away—even while the violence of the act functions like a bludgeon to keep other proletarians working, or at least pacified.

The difference between the Baltimore of today and the Baltimore of 1800 is that this merciless process—the masking of crises—is now very much out in the open, almost celebrated in the same way the city celebrates its “firsts.” Since 1807, when international slave trade was made illegal in the US, Baltimore could only function illicitly in this industry, its slave jails filled discretely. Today, not only is the disproportionate jailing of blacks legally condoned, in Baltimore it has become accepted as a fact of life. The manufacturing and concealing of capital’s crises has become a full-blown industry, part of Baltimore’s so-called culture (ie, The Wire). As a system for the management of black bodies, it is growing.

Infrastructure is a gauge of this. Baltimore City Detention Center (BCDC) is one of the largest municipal jails in the US, established well before the end of slavery, in 1801.[xiv] The center carries with it a legacy of racialized confinement and brutality. Every year it processes over 73,000 people and locks up more than 35,000. Nine out of ten inmates are black. Like a billboard, the façade of the Central Booking and Intake Center runs right along I-83, with some of its tiny cell windows facing outward. White kids pass it on their way downtown to bars or to an O’s game. Black kids can see it from “The Block” and are reminded by a huge red banner to “drop the gun or pick a room.”[xv] Here, the violence of capital is on display. It becomes part of the daily commute—forever affirmed.

This is because, in Baltimore and elsewhere, imprisonment provides the threat by which surplus population is managed. It’s a way of saying “we can make you black.” It also offers an actual drain on this population, removing bodies from the possibility of wage labor. For the reproduction of capitalist relations, this becomes vital in a place like deindustrialized Baltimore: it prevents the chronically unemployed from getting too large or powerful. This explains why in 2010, during the thick of the recession, it did not appear illogical for Baltimore-City officials to propose spending millions of dollars on two new jail facilities. It is also part of the reason Baltimore’s homeless population increased 19.7% during the recession, from 2009 to 2011. As in all of capitalism’s crises, people didn’t just lose their jobs. While some became unemployed and easily exploitable, other were cast into—or confined within—the excess of the unemployable. This is always a racialized and racializing process, especially in Baltimore, where blacks make up the majority of those sent to jail, of those forced out of the wage relation in one way or another.

When the Mondawmin kids picked up rocks they were saying NO all to this—to a past that keeps on repeating itself. “Our parents were dealing with the same shit.” They were saying NO to the guns pointed in their faces every day forever, and to the courts and prisons and smiling politicians behind those guns and rich motherfuckers behind it all. “Let’s show them how it feels to be beat up and attacked … Enough is enough.” They were saying NO to the “firsts” that evict them from their homes, close down their recreation centers, and allow for suburban whites seemingly distant from the conflict to #prayforbaltimore on twitter and to “send love to the community of Baltimore.” But there is no community and never has been: that is the thesis of the riot, if any. There is no need to vacillate here, the riot demands decision. Those who came in last have every right to burn the city of firsts in front of the eyes of those who would pray for it. I say: #prayforfire.

Why West Baltimore?

Much has been done to tie racial issues in Baltimore to the city’s social and economic past. I won’t repeat these arguments in detail, but just note a few quick facts: until very recently Baltimore’s population (622,793 as of 2014) had been rapidly declining from its peak of 949,708 in 1950. Like similar industrial cities in the Northeastern rustbelt, Baltimore’s loss of population went hand-in-hand with its loss of manufacturing jobs beginning in the early 1970s.[xvi] Overall, the city lost a total of 100,000 manufacturing positions between 1950 and 1995. Despite widespread propaganda about foreign workers “stealing jobs,” the fact is that a significant portion of this deindustrialization simply came through mechanization and the associated construction of hyper-efficient logistics networks and computerized, “on-demand” forms of production. The US remains an industrial powerhouse in terms of output, but, like many other countries, its manufacturing employment has dwindled. Baltimore is continuing to feel the effects of this, as its unemployment rate (8.4%) remains above the national average (5.5%). But this has impacted blacks much more significantly. There are more than three times as many young black men unemployed, ages 20 to 24, than there are white men in this age range. And, at $33,000, median income for black households is just above half of what whites make in the city.

Most of those who survived deindustrialization in Baltimore were white-collar workers. Today the city’s largest employer is Johns Hopkins Hospital. Other large companies downtown include Legg Mason and T. Rowe Price. As in similar US cities, Baltimore’s industrial working class was decimated. What was left of it was largely deskilled: 90% of jobs in the city are now low-wage positions in the service economy, including the tourism industry which grew since the Inner Harbor began redevelopment in the 1970s.[xvii] After the Baltimore riots of 1968, even white proletarians began moving to the suburbs, albeit poorer ones. The black working class was left behind to stagnate in areas where industrial infrastructure had been gutted, having few employment options beyond low-paying service jobs.

Obviously these geographic factors have had an enormous impact on Baltimore and are at the foundation of the riots we’re seeing today. But I’d like to be a bit more specific. To date, most of the rioting has happened in West Baltimore, although there has been significant looting throughout downtown. The most notable events—rock throwing, car burnings, the picturesque CVS fire—have clustered around Sandtown-Winchester. This is the neighborhood where Freddie Gray grew up, where he was arrested on April 12th, and where his funeral service was held on April 27th.

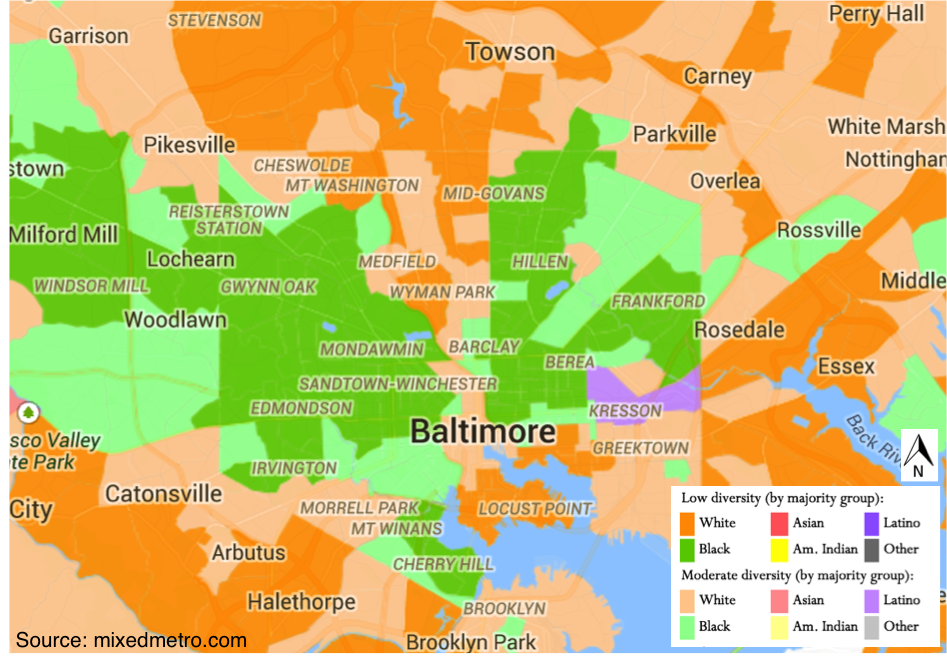

West Baltimore has a population of about 52,000. Completed in 1982 but first planned in the late 1960s, Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard sequesters many of area’s projects from the bustle of downtown. But this segregation is more than architectural. West Baltimore is over 85% black, much higher than the citywide average of 64%. Its median income is $27,302, while Baltimore’s is $38,721.

Located on the eastern side of West Baltimore, Sandtown-Winchester presents a much more dramatic case. It is 97% black and its median household income is $24,000. Over half of its residents between the ages of 16 and 64 are jobless. For individuals under 25 median income is only $14,149. Poor and non-white, the neighborhood is a crucial site at which the contradictions of capital are managed, as a staggering proportion of its residents have been disciplined and tossed out of the wage relation. In fact, Sandtown-Winchester leads Maryland in having the highest number residents imprisoned, at 458. This is roughly three percent of the neighborhood’s population and is a massive expense for the state. Maryland allocates $17 million to the neighborhood each year, all of which goes to incarceration.

As in other poor areas of the city, residents of West Baltimore have been subject to forced evictions and periodic disinvestment. In the 1960s, plans to expand I-70 through West Baltimore displaced 960 black families from their homes. Known as the “highway to nowhere” this project was never completed and is now part of US 40. More recently, in 2013, the city announced its decision to exercise eminent domain to force residents, many of them black, from their homes in Upton/Druid Hill—not far from the rioting. A Baltimore Sun article on the displacement frames the topic in a predictable way: “Some residents are suspicious of the process that will take their homes. Others can’t wait to rid their neighborhood of blight, perhaps Baltimore’s most visible problem.” Translated: others can’t wait to make poor blacks invisible.

Forced eviction is not the only problem, and the rioters themselves have been far more eloquent than the Baltimore Sun in explaining the scope of the devastation. As one of the April-27th rioters put it, “There’s nothing really here for us. Even the youth. There’s no recreation centers, no escape.” Many of the protestors mentioned this: that Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake has recently pulled the plug on several recreation centers throughout the city, as part of a $500,000 cut to the budget of the Department of Parks and Recreation. In August of 2012, she announced the closing of four centers, all of which were in West Baltimore: Harlem Park, Central Rosemont, Hilton, and Crispus Attucks. By 2013, about 20 of the city’s 55 rec centers had been terminated on account of the mayor’s plan to consolidate funding. Education has also been hit. The city board voted in 2013 and 2014 to shut down twelve schools—five are in West Baltimore.

These schools don’t have anywhere near the resources of private schools in north Baltimore. Most of the latter have multi-million dollar endowments (my former school’s is $133 million). Several have indoor pools, brand-new buildings, spiffy stadiums—one even has a roof observatory. Meanwhile, many public schools in the city lack basic heat and air conditioning. With this kind of ridiculous disparity, along with their schools being cut, it’s no surprise that students in West Baltimore are pissed off. Nearly half of high school students in Sandtown-Winchester are chronically absent—which is why so many had the time to do more important things like hurl rocks at cops.

In a curious twist of cause and effect, the riots provided a means of blaming this already-existing austerity on the rioters themselves. During the fires, community leaders went on-air to say that they had no idea why the youths would burn the very infrastructure on which their futures depended. Pastor Donte Hickman Sr. (pastor of the church that burned) argued on CNN that the rioters were “insensitive to what the church and the community was doing here,” and that the focus needs to be “on how we rebuild.” Other news programs underlined how the fires and looting would destroy services and jobs, taking money away from schools and recreation centers, and keeping the poor in the same state of austerity they brought upon themselves in the first place. But even as civil-rights types began to rewrite the riots as the original sin of the city’s austerity, the actions of the “juveniles” offered a different argument: this “development” has never and will never change any of this, at best acting as a distraction from the systemic inequalities that keep blacks in Baltimore in a position of immiseration, whereby a few “community leaders” might step up to scramble for crumbs from an ever-shrinking surplus.

“We fall and we keep getting back up,” Pastor Hickman argued. Graciously, he wished to grant those who started the fire “another chance,” to provide them with “a job, and with an opportunity, with an affordable living […] This is not about a building,” he preached, “this is about change. This is about hope. This is about restoring the dreams and the lives of people in the community that feel like there is no hope.” But this is precisely the ideology of optimism that the riot torched, revealing it to be worthless. If anything, we all need to fall and keep falling, to fall so hard that everyone falls with us.

Because what is the price of hope? With his church still in flames, Hickman pled for “private investors to come in to East Baltimore and change it for the better.” In a city that since 2002 has championed the slogan “BELIEVE,” hope is just another entryway into a system of brutal exploitation and surplus extraction. During the riots, the term was forced on people almost as a threat—framing the rioters as “juveniles” who should know better, who should think carefully about and invest in their futures. All that burning and looting could ever do, in the eyes of Hope, is to place these futures at greater risk. But what exactly is a safe future? It’s one that’s been made manageable.

The future is already fucked, let’s admit that much. As one protestor said, “At the end of the day, as far as this earth is concerned […] there’s a lot of Freddie Grays, there’s a lot of Mike Browns, and everywhere there’s a lot of racism. It ain’t never gonna change. It ain’t never gonna change. And I’m telling you to your face, to the camera, to the media: ain’t shit gonna change.” There’s no way off this “earth,” this eternal return of the same, until we burn it the fuck down.

Why Kids?

The progressive move, then, has been to shift the terms of debate from “thugs” to “frustrated youth.” It was a group of high-schoolers, after all, who triggered the riot when they poured out into the streets of Mondawmin to toss rocks at cops. Presumably, they were acting in response to a message on social media calling for a “purge,” a reference to the popular movies The Purge (2013) and The Purge: Anarchy (2014).

Why was this vision of “lawlessness” the go-to fantasy for the kids in Baltimore? In the movies, which take place in a future America, the “purge” is a 12-hour period during which all crime is legal and all health and law-enforcement services are suspended. The rationale for the purge is that, in offering one night of violence and cathartic release, the country can successfully manage to reduce social ills such as crime—portrayed as if they are the simple result of over-brimming passions that need some sort of release.

Most of the media reports on the riots tended to only focus on this aspect of the movies. They posed the high-school kids’ actions as directly and uncritically carrying out a Hollywood vision of a world without laws, as destroying shit for the fun of it. In the films, however, it becomes increasingly clear that the purge is essentially a method of mass-executing people in poverty, often by death squads. In both films, but especially in the sequel, this takes on racist overtones, as poor blacks are auctioned off to rich bidders who murder them or hunt them for sport. A small army of black militants seizes the opportunity to fight back and bombs a white hunting party. The attraction of the #purge as a symbol, therefore, becomes much more complex. Can it not be argued that the idea of the purge resonated among youths precisely because it spoke to their position as targets of an ongoing and very real assault on poor blacks? Isn’t the “purge” simply the crisis itself—and the evisceration of surplus bodies via police, prisons or mind-numbing labor? To call for a purge, then, means simply to recognize one’s surroundings and, in so doing, to become capable of acting against them.

But why was this need—the need to riot—realized first and foremost by a group of youths? Why did the riots of April 27th start with them and not others—not, for example, the older residents of the neighborhood who had experienced years upon years of corruption and brutality, who had known in their lives maybe a hundred Freddie Grays before this one? In Baltimore, like everywhere else, resources are distributed unevenly not only across neighborhoods, race, and county lines, but also across different age groups. This has nothing to do with age in itself but with age as a position within a set of material relations, and these material relations are themselves structured by the sediment of history. In West Baltimore, for instance, it is predominantly the youth who are disadvantaged by the loss of rec centers and the closing of schools, and of course it is the youth who are the primary targets for police attacks. While many of their older siblings have already been siphoned into America’s bottomless prison system, the “elders” left in the community are those who have learned that, in order to scrape some marginal survival from the city one needs to keep one’s head down—for them, Freddie Gray’s mistake was to look the cop in the eyes.

By evening on the 27th a stark divide had been drawn between the kids willing to smash whatever and the older protestors who said “it just makes us look bad” and that “it’s a quick death, it’s quick incarceration.” Those who condemned the high-schoolers did so on the grounds that violence will only lead to another Freddie Gray: “we don’t want the police hurting anyone else.” What we really need, they argued, were education and jobs. A familiar argument the kids had no trouble seeing though. They understood that the riot is the only choice, that there is no longer any way to walk softly and hope to get by.

In a bizarre way it soon became clear, despite rumors to the contrary, that within the riots themselves the most reactionary protestors were the senior Bloods, Crips, and Nation of Islam members who guarded storefronts, called for peace and order and even stood between protestors and police.[xviii] In the face of the riot, the gangs did not reunite in the shape of the Party that birthed them, but instead showed themselves to be little more than cops without badges. “We don’t really need [the police],” said one Bloods member, “We can do this ourselves. We can police them ourselves.” This serves as a worthwhile reminder that the avant-garde of the police, deployed in the most uncontrollable of capital’s frontiers and wastelands, has always operated beyond the scope of its own law. Here order is enforced through direct violence, often carried out by those recruited from the wastelands themselves and always operating under the veil, again, of “community.”[xix]

This is not an actual generational divide so much as a simple faultline in how the crisis of capital is managed. Unlike their “elders,” young people in Baltimore were born into a post-welfare state, reaping none of the benefits available to those who came before. Growing up in a world of austerity, they provide a pool of cheap and exploitable labor, and as such have played a vital role in whatever “recovery” the economists detect. This “generational” split—which is really just the time-sequenced return of class, in the old-school sense of the word—is therefore the means by which capitalism implements and justifies its expansion within a climate of debt and budgetary restrictions following the latest sequence of recessions.

But, as is clear in Baltimore, “generation” works differently when filtered through race. Blacks never fully got to be “baby boomers” in the first place. Many were denied jobs on the basis of skin color, and nearly all were barred from the post-war suburbs and attendant boon in home equity.[xx] Others were tossed in jail as the rate of incarceration exploded in the 1970s when most “boomers” were reaching adulthood. Among the first to fill the prisons were, precisely, members of the more militant Black Power organizations, many of whom were subsequently murdered, while others remain there to this day. In the Freddie Gray riots, the cautionary “elders” were those left standing—those who are neither dead nor in prison. They were people like Pastor Hickman who had reformed their once-deviant behavior, had accepted the lessons of the aristocracy. And that’s what the idea of “generational divide” serves to do: to reproduce the image of the prodigal, black youth in need of correction and discipline. As one politician put it: “Where are the parents of these kids? Where are the adults and community pastors? Why are these kids responding to this call for violence instead of heading home and preparing for end of year final exams?”

Race and Aristocracy

Coming-of-age also plays an important role for Baltimore’s rich whites, as we have seen with the Bachelors’ Cotillion. Yet the Freddie Gray riots force us to rethink how exactly the city’s aristocracy is constituted, how it handles and negotiates lines of race, and how it works to manage crisis. Old-Regime traditions like the débutante ball, or southern ones like the Hunt Cup, produce an aristocratic divide under which the “middle class” becomes decreasingly “middle” and is again secured firmly within a reinvigorated racial hierarchy. This reinvention (or dissolution, depending on one’s taste) of the “middle class” is, of course, a feature of today’s skyrocketing inequality. It functions not only to produce precarious workers (those who fall out of or can never enter into the “middle”) and to justify wage theft after the recession, but also to ensure the existence of a “lower” or “nonproductive” class of bodies who may be disciplined and removed from civil society if need be. These are defined by their “criminality” relative to lawful society. In some places, the “creative” class is thus constituted by the “criminal” one composed of the hi-tech sector’s own residue of mechanization. In Baltimore, however, “creativity” is not required.

What distinguishes Baltimore from many US cities is that this management relies on the renewal of slave-era structures. In places like New York, the Bay Area, Seattle, Los Angeles, and Atlanta, inequality has been produced and maintained in recent years largely under the guise of “multicultural” projects, where multiple interest groups are allowed access to some small foothold in the narrower “creative” classes that have replaced the “middle class.” But Baltimore has no large tech industry or sexy startups through which to disguise the ruthless extraction of surplus. There, the destruction of the “middle” has occurred by other, more visibly racial, means—by mining a colonial past.

Yet the stakes are different than they were in 1800: race is conceived differently. White aristocracy doesn’t always appear in such an obvious form. The city’s mayor, its police commissioner and state’s attorney, are all black. And, unlike in Ferguson, the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) is almost equally split between blacks and whites. What this shows it that today Baltimore’s aristocracy—along with what supports it—is not based on racial difference. Inclusion is not only compatible with management, but is a necessary component. Instead, the aristocracy is built on a logic of racial domination, on a material process that racializes incarceration, warfare, and violence regardless of the skin color of those who carry it out. Race becomes, in Baltimore and elsewhere, the limit point of capitalism—that which imparts sovereignty to the state and its actions, but also that which must be constantly attacked in order to expand the reach of globalization and increase the growth of profit. Racial violence, in other words, is a rite of passage in the movement of capital, its own cotillion.

Tactics

Some have realized the only way out of this situation is to crash the party. Since at least the Arab Spring, it’s undeniable that we are living in a new era of riots. And, since Ferguson, these riots have taken a racial turn in the US. The events in Baltimore further this trend, developing existing strategies of insurrection and producing new ones.

One of the reasons why the riots of April 27th were able to spread and to sustain themselves into the night is that, like other recent riots, they caught police off-guard. Heeding the call to “purge” that circulated on social media, large numbers of high-school kids turned out in the streets of Mondawmin to fling rocks at police. From here the riot expanded, from rock-throwing to looting stores and burning cop cars—too many kids for the police to handle. As Baltimore City Police Commissioner Anthony Batts admitted bluntly, “they just outnumbered us and outflanked us.” This follows a recent trend of loosely coordinated “flash robs,” where groups of usually 20-or-more teens enter convenience stores or retail shops en masse to ransack merchandise. These have occurred over the past few years in Chicago, Portland, DC, Las Vegas, Jacksonville, and Houston.

Yet, at the same time, the BPD was not entirely unprepared. Before the events of the 27th, they were alerted via social media to the threat of a “purge.” This distinguishes the Baltimore riots from those of London in 2011 where rioters relied largely on Blackberry Messenger rather than Facebook or Twitter in order to communicate beneath the radar of police. In Baltimore, on the other hand, the distribution of #purge messages on social media created a spectacle for those on both sides of the law. And it was in part the reaction of the police, some throwing rocks right back at the high-school kids, that escalated the riots and caused them to spread to individuals in older age groups.

High-schoolers posed a threat to cops in terms not only of their numbers but also their weaponry. Quite simply, they were able to find and collect an abundance of bottles, rocks, and bricks for throwing—and their aim was impeccable. Baltimore City’s landscape is essentially a treasure-trove for the discerning rioter.[xxi] With roughly 16,000 vacant buildings and 14,000 vacant lots, there’s plenty of rubble lying around. Baltimore was also once, in the nineteenth century, a major center for brick-making. In 1881, an historian wrote that the “Baltimore press brick is almost as well known as the Chesapeake oyster.” Indeed, in the same year, it was estimated that the city produced an annual total of 100,000,000 bricks. Apparently they were quite good. In 1833 Charles Varle claimed that “the best bricks in the US are manufactured in Baltimore.” Many of these “Baltimore Bricks” now reside in the city’s famous rowhomes. Others have since left bruises on the bodies of cops.

Another tactic that emerged on the 27th was the cutting of fire hoses. Obviously this prolonged the duration of fires, but it also caused a fascinating ideological breakdown among clueless reporters who saw the cutting as an act of self-sabotage, of rioters destroying what was meant to save them. Faced with such a brazen “fuck you,” the reporters earnestly could not understand what was happening. They saw only an opaque, wordless void. It didn’t make sense. What burned in East Baltimore included the construction site of what was to become a community center and 60 senior-citizen apartments. To the latter, the city had lent $15 million. For everyone from latte-sipping social democrats to tight-belted neoliberals, the fires and the cutting appeared as the ultimate waste—pure irrationality—defying the logic of everything that should happen. And this is precisely why the cutting was an effective tactic: it kept fires burning, but, more importantly, it also confronted the complacent with something they could not understand on their own terms. Unswallowable. The tactic of cutting fire hoses forces those who encounter it to a final decision: accept the irrationality of the riot or reject it all together.

That’s what an effective tactic does. For those who side with it, it rules out the possibility of reform or progress under current structures of mediation. We don’t want your shitty low-income apartments, the fires say. We want to incinerate every last remnant of a dying generation—from the convenience stores where we give our money to a system that casts us aside, to the churches whose leaders tell us we have sinned. From the apartment buildings where we go to live, to the senior homes where we go to die. For so long we have paid the rich in complacency, and when we have not we have been shuttled off to prison—to smolder.

The final tactic has clear implications for many other US cities: the conjunction of riots and professional sports. On the 25th the proximity of rioters to Camden Yards proved explosive. A similar but non-physical interaction occurred last year in St. Louis when Michael Brown supporters encountered drunk Cardinals fans outside of Busch Stadium. In both instances, many white baseball fans revealed themselves to be belligerent racists. In St. Louis, fans yelled at the protestors to get jobs and to “pull up your pants!” In Baltimore several bar patrons attacked protestors outright. This isn’t to say that fistfights with white sports fans are particularly fruitful, just that they have been a notable moment in recent events that cannot be ignored. This is because the conjunction of protests and sports in the Baltimore and St. Louis cases revealed exploitative, not to mention painful, class and race relations that would otherwise simmer below the surface of the everyday. Unsurprisingly many fans reacted to this violently. Like the Under Armor-sponsored chant played at Ravens football games, the riot demanded a vow of defense: “Will you protect this house? I will.” This was one of the hashtags used in reference to the riots: #protectthishouse.

Couvre-Feu (Counter-Tactics)

Two days after Baltimore was placed in a state of emergency, #protectthishouse was taken to a very literal level. On the 29th the Orioles played the Chicago White Sox in what would be Major League Baseball’s first ever game played in an empty stadium. After postponing the previous two days’ games, the League decided enough was enough, that the Orioles might be at risk of not being able to play all of their 162 games. So they created a controlled environment: a stadium without fans. In the 2010 World Cup, the North Korean team was cheered on by Chinese actors hired by the government, since North Koreans were not allowed to leave the country. In Baltimore, we see the opposite, but still with a touch of North Korea. The state of emergency was upheld—the movements of bodies restricted—while the games were allowed to continue. This is ideology at its purest. The spectacle must go on or else the Hunger Games ideology-engine stops and we can suddenly see how fucked we all really are.

Besides getting everyday life up and running again, one of first actions taken by Baltimore’s mayor was to impose a weeklong, 10pm curfew. Similar measures have been instituted in other recent riots, like the midnight curfew enforced in Ferguson after the shooting of Michael Brown. The term “curfew” is interesting because of its connotations with youth. Malls in the US, for instance, often have curfews restricting minors from entering after certain times. Many of us growing up, I’m sure, had to rush home at least once to “make curfew.” Does this word, when imposed on a city, not reduce all individuals to children—to delinquent juveniles?

The term curfew itself comes from the French phrase couvre-feu, meaning “cover the fire.” In Baltimore the word once again takes on its original meaning. And to quash the fire is also to quash the youth that started it. For in Baltimore, the youth—Generation Zero—have become identical to the fire itself. This is realized, and admitted to, in the imposition of the curfew. Faced with this, the task is always to keep this fire burning, to break curfew, to refuse to forget that something impossible has happened, that a group of people were, for an instant, made into flames.

No Lives Matter

Today, the riot is a necessary form of struggle. In our current moment, non-violence as a tactic has become increasingly futile, if it ever had any use in the first place. It’s no coincidence that race riots today in Baltimore appear as a flashback to those in 1968. 2015 is 1968, only worse. All insurrectionary tactics emerge from specific material contexts. Tactics are not models advocated for in some sterile congress of ideas, from which citizens or consumers might choose the most favorable option from among all those stocked by Amazon or the Electoral College. Tactics are operations conducted in an immediate terrain, by actors whose interests are disparate and often deeply personal. At best we can, as I have attempted to do above, approach such things in a descriptive manner—learning from them for next time, rather than attempting to measure them as if we could force-fit them to some different shape.

In the context of Baltimore today and of other US cities, peace means letting things go back to the way they were. Peace means wishing that we could all just get along already. Peace means: #alllivesmatter so why the big fuss? But if we have learned anything over the past few decades it’s that tolerance, inclusion, and the celebration of diversity in and of themselves don’t get us anywhere, acting more often to disguise and condone their opposites. They are what allow all genera of despicable motherfuckers to appear as if they’re addressing real issues without actually having to confront them. To tolerate a “culture” or “way of life” is to treat that subject as a given and to refuse to investigate the ongoing processes of exploitation on which it is structured and the histories that generated it. This is why non-violence and tolerance are, in the Baltimore situation, purely reactionary: they depoliticize the struggle and seek its resolution. They are the equivalent of calling for an amnesty parade while bombs are still being dropped overhead.

The idea that violence defaces the original message of the Freddie Gray protests, along with every other movement, simply misses the point. As we saw in 2011, beginning with the Arab Spring, the modern riot is most effective not in its ability to relay a coherent message or to make demands, but precisely in its lack of message. Why must frustrated black teenagers in Baltimore city have a clear message? To say “they have no goal” or “they should be peaceful” is to place brackets around the protest. It is to sanitize the riot (“it’s not a riot it’s a rebellion”) in a way that prevents it from undermining race, class, and gender hierarchies. We must realize that there is no movement or message. That there are only people on the streets making shit happen, those trying to stop them, and those who haven’t (yet) been faced with the decision to act.

Besides, how can a struggle have a clear goal when it is trying to produce something qualitatively new, beyond the material relations through which we understand it now? What the riots in Baltimore acknowledge is that the only way out of the present, even conceptually, is through its destruction—even “if it takes us to burn this whole city down.” Those who oppose the riots, to whatever degree and with whatever intention, implicitly affirm the relations which keep blacks in Baltimore and elsewhere in positions of immiseration. This is also why #alllivesmatter is completely reactionary. Because to say that something “matters” is to uphold the material conditions under which it appears. It’s to argue that the problems in Baltimore are ultimately those of intolerance and a lack of education, that if everyone just appreciated everyone else we could all live together in harmony.

Here is an alternative: #nolivesmatter. Instead of the issue being a moral one (ie, either some lives matter or all lives matter) #nolivesmatter means that what is happening today in Baltimore has nothing to do with belief at all. The city’s problems, like all others, exist regardless of how we choose to feel about them and what meanings we attribute—they exist regardless of what “matters.” It’s only when we abandon the search for meaning that we see what’s going on is that certain groups of people are getting screwed over for the benefit of others. Right now in Baltimore, amid the unrest, it’s apparent that calls for peace, prayer, and community are another way of saying: bring me back “Baltimore,” bring me back to a place where I don’t have to see this kind of suffering. This is why so many of my friends have changed their facebook backgrounds to tranquil pictures of the Baltimore cityscape. It’s an act of denial, a desire to tell oneself that the life I had been living up to this point—that my home—was not built on the backs of black youth, that we are not all yoked to that reasonless machine called the economy, shedding human lives like so much dead skin. We all know now that this is delusion. Because, for once, something has pierced through the everyday screen of ideology. For once, something has happened. It has come, been made palpable, in the form of the riot. Now is the time to follow out its consequences.

Because without the riot what do we have to fall back on? We have the empty stadium, its cleanliness, where the national anthem is played on repeat for no one. We have jails for all nine circles of hell, overflowing with black bodies for eternity. If they listen carefully they can make out the pounding of hooves on the ground overhead—the endless horserace, the waltz of the aristocrats. From the vibration, clumps of soil, dust, and flower petals begin to fall on the skulls of those below, covering them in blankets of rubble again and again. This is a world—the one we’re living—that dreams of burial, of a frozen gutter where nothing ever happens. It dances to keep everything in place.

—Key MacFarlane

[i] In strange counterpoint to the highborn Bachelors Cotillion, Hartford County’s Black Youth in Action group has their own débutante ball for young girls of color.

[ii] The first fatalities of the civil war happened on Pratt Street in April 1861 during a clash between anti-War Democrats and Confederate sympathizers. After the riot, in order to forestall a Maryland secession, Lincoln declared marital law in the state and sent federal troops to occupy Baltimore. “If quiet was kept in Baltimore a little longer,” Lincoln wrote, “Maryland might be considered the first of the redeemed.”

[iii] And, of course, whites-only country clubs.

[iv] Those who insist that “the cops must have started it,” completely miss the point here. Even if it’s true that the police instigated the initial attacks (and it’s certainly probable), the moral logic of this argument is one that invalidates violent attacks against the police in and of themselves—the presumption is that, if the police hadn’t instigated the attacks, then these attacks would not have been justified. Similarly, the displacement of the violence onto the police—people arguing that it’s really the “police who are rioting”—tends to nullify the subjectivity of the black youth engaged in the riot. Mirroring the logic of racial power itself, these young people are no longer active agents, but simple reactive bodies on which police violence is exercised. Rioting is, in its simplest form, the execution of a chaotic collective will. The fear of acknowledging the riot, re-rendering it as a “protest,” a “movement” or a “rebellion,” simply confirms the racializing gesture in an attempt to deny blacks any kind of subjectivity capable of targeted, willed violence against an enemy.

[v] Camden Yards had also become a battleground during The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, among the first major strike waves in US history. Echoing current events, the Governor of Maryland called in the National Guard to quash the strike. The Guard fought their way to Camden Station, killing 10 and wounding 25.

[vi] The big three gentrified neighborhoods in Baltimore are Fells Point, Federal Hill, and Canton.

[vii] Currently, the tuition for this school is $28,110 (high school). This is not the highest rate among private schools in the Baltimore area.

[viii] This means that I’m not at all attempting to speak “for” those engaged in the riots, where people were doubtlessly acting on a wide variety of impulses the depth of which only they themselves can understand—and in many cases, they have been articulate enough when faced with idiot reporters. The point, then, isn’t to diagnose what the riots were really “saying” – riots don’t communicate a “message” – nor to step in for the “inarticulate” or “unheard” youth to make their message clear. Instead, the point is that people like me have been generated by the crisis as much as the riots themselves, and we are tied to these geographically distant events by a certain affinity of the era. This is an inquiry into that affinity and its consequences.

[ix] From 1980 to 2008 the number of people incarcerated in the US has increased fourfold, from 500,000 to nearly 2.3 million people. This makes up 25% of the world’s prison population.

[x] Latinos should not be ignored here either. In 2008, 58% of all US prisoners were either black or latino, despite these groups making up only about a quarter of the nation’s population. 1 out of every 15 black men and one 1 of every 36 latino men are imprisoned. For white men, this is true for only 1 in every 136 (see here for a graphic illustration).

[xi] This is the case for 1 in 6 for latino men and 1 in 17 for white men.

[xii] Things look bleak as well for women, as the number of those incarcerated has risen 800 percent in the last three decades. Unsurprisingly this has occurred unevenly across racial lines: black women are three times more likely to be locked up than white women.

[xiii] Today, Roland Park remains one of Baltimore’s most exclusive neighborhoods at just below 80% white (compared to the citywide rate of 31%) and as of 2011 having a median household income of around $118,000 (compared the Baltimore City’s overall level of $38,700 at that time).

[xiv] The center is home to another historical milestone: established in 1811, the Maryland Metropolitan Transition Center (formerly the “Maryland Penitentiary”) was the first state-sponsored prison in Maryland and the second of its kind in the country.

[xv] BCDC is also a constant reminder to the city’s homeless, with Our Daily Bread located in a building just behind the jail—donated by Orioles owner Peter Angelos.

[xvi] Under the ownership of Bethlehem Steel, the Sparrow’s Point steel mill once produced over 8 million tons of steel and employed over 30,000 by the end of the 1950s. Beginning in the 1960s, plant employment began to decline in the face of cheap foreign steel and a shift in the industry towards oxygen furnaces and scrap recycling, further mechanizing the production process. In 2001, Bethehem Steel filed for bankruptcy. The Sparrow’s Point mill is currently in the process of being demolished.

[xvii] For a critical account of the commercial development of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor see David Harvey, “A View from Federal Hill,” in The Baltimore Book. Temple University Press, 1991. Many of Harvey’s arguments are restated in this talk. Notably, Harvey situates the redevelopment as a part of a reaction against the 1968 riots, as a means of bringing people together and convincing them that Baltimore was a city worth being part of. He also makes the point that some of the Inner Harbor’s architecture—like the building that houses the Maryland Science Center—was designed to keep out “dangerous” blacks.

[xviii] The same pattern was observed in Ferguson, where the New Black Panther Party stepped in to restore order, directing traffic, preventing people from attacking police, and telling women specifically to “go home” and leave the work to the men.

[xix] This is also a cautionary note for leftists who tend to idealize the role played by “grassroots” forms of survival and affinity in these zones. Surviving conditions of extreme brutality requires brutal measures, and the type of nobility many leftists expect from “the oppressed” is among the first things sacrificed on the altar of necessity.

[xx] It was precisely this home equity explosion, via the GI bill, that finally transformed former non-white groups such as Southern and Eastern European immigrants, into full-fledged whites. This material inclusion was the final act in a series of racial ascension protocols that had been enacted for these workers throughout the 20th century, beginning with the “Americanization” campaigns of the early 1900s, and always taking place in distinction to what was (more often, wasn’t) afforded to blacks.

[xxi] This kind of strategic and improvised use of the landscape carries echoes of other recent riots, such as the ‘09 Oscar Grant riots in Oakland where protestors took advantage of trash collection day and set fires to dumpsters and trashcans.

May 14, 2015

A masterful analysis, comprehensive and frightening.

May 14, 2015

Thank you for putting in such clear perspective the Baltimore in which we both were raised. I left when I graduated from Gilman, and never looked back, but I have never been able to explain the awkward suffocation I have always felt in Baltimore and the discomfort I start to feel just as the Amtrak train passes Johns Hopkins Hospital before it enters the long tunnel to deliver me to Baltimore Penn Sta. I get it now. We are all so fucking fucked, and you hit the nail right on the head. You’re a genius and my new hero.

May 17, 2015

Thought this was really really good. Recommended it here: http://dialectical-delinquents.com/latest-articles/

Just a few related questions to the author: you came from that upper middle class white Baltimore background – how and why did you break out of it? What do you perceive as the weaknesses, the vulnerable spots in the cohesion of the lives of people from that background that could maybe be attacked to make more people from that background break away from it (or at least have breakdowns)? And what has been the reaction of your friends – the ones who put up pictures of a peaceful Baltimore on their Facebook pages – to this text – or have you not shown it to them?

– Sam

PS You put up a link to Woland’s “the era of riots…” I presume you’ve seen this: http://dialectical-delinquents.com/war-politics/the-minister-of-sic/

May 27, 2015

Hi Sam,

Apologies for the LONG-overdue response to your questions. Unfortunately I don’t have a very good story for how or why I broke out of my background. Partially this is because I’m not so sure I have completely — or that such a clean break would even be possible. It would be a mistake to say that writing an article on Baltimore means anything, either in terms of my positionality or that of the people around me. But that’s the point, isn’t it? That we’re all fucked regardless of where we think we are politically. Because, at the end of the day, whether or not I disavow my “background,” it still exists as a set of material consequences that screw certain people over. I can never *fully* separate myself from this, no one can, until the mediations are destroyed that make such a background possible, or even thinkable. To believe otherwise would be to reaffirm these mediations, even while rejecting them in writing.

That said, I do think that Baltimore presents a set of socioeconomic and racial contradictions that is very hard for white elites to ignore in full, which perhaps explains why someone could “break out.” It’s not that these contradictions don’t exist in other US cities – of course they do. But in Baltimore they’re often more palpable than most, especially for those who live downtown. Geographically, in terms of rich and poor neighborhoods, Baltimore is fairly patchy, meaning that it’s very difficult to drive from one location to the next without experiencing ridiculously obvious disparity. From where I lived in Baltimore (in Upper Fells) many of my friends were scared of going just one block north, too many blocks east, or a few blocks southwest to where some of the projects were. Unlike a city like Seattle, gentrification in bmore has not gotten to the point where white yuppies have an entire sphere unto themselves: most still drive though non-gentrified areas on their way to work, or at least have to deal with the city in one way or another.

Much like the riot, I think the geography of Baltimore confronts everyone with a decision. For white elites, the choice (which is a rejection) has usually been one of segregation and security, of increasing prison populations (like the $30M youth jail that was recently approved) and cloistering in the county behind aristocratic institutions like the Hunt Cup.

So to answer your question about breaking away, perhaps we could do more to develop tactics that force this decision, confronting white elites with the (hopeless) reality that is Baltimore, that is the racialized process of capital itself. And not to do this through The Wire, a news program, or even an Ultra article, but from the streets. Fewer mediations. The riot is a fine tactic for this, but certainly there are others.

As far as weaknesses to attack, these would include the institutions that aristocrats depend on for existence (eg, hunt cup, lacrosse, etc.). Of course, these are not “immoral” or “unethical” in and of themselves but rather in the way they function in support of an ideology that rejects what’s going on in Baltimore. They are weaknesses because they can be shown – quite literally — to be false (but not immaterial), in the sense that they work to obscure the truth that something like the riot makes appear.

And I think some people from my background are not that far from “breaking away” or from recognizing ideology for what it is. The article above made the rounds on facebook, was commented on by many of my friends. I was more than surprised by a few of the responses I received. People I never thought could get behind “the riot” expressed their solidarity. Some said they were “coming around” to the insurrectionary position and to its consequences.

However, facebook was problematic in garnering response. For one, very few people expressed their outright disagreement with the article, perhaps because they were being polite or because social norms prevented them from doing so. This shows how social media, in and of itself, can never force a decision. Like watching The Wire, my friends on facebook could choose to read the article or not, respond to it or remain in silence. And in some sense, the act of sharing relegates the article, along with the riots in general, to another “event” on someone’s timeline – stable, secure, and cleansed of every danger. It’s a space where insurrection can be “tolerated” at a distance and eventually forgotten.

Sam, I hope this response manages to address some of your questions. It probably could have been done in far fewer lines!

Many thanks to you and to everyone for their feedback on this.

key

June 29, 2015

Hi KM –

Apologies for taking so long to respond to this: didn’t see it for some time, then forgot to respond, etc. etc. In the end I don’t have much to say, except thanks for responding, but the following seemed like a bit of an evasion of the problem:

at the end of the day, whether or not I disavow my “background,” it still exists as a set of material consequences that screw certain people over. I can never *fully* separate myself from this, no one can, until the mediations are destroyed that make such a background possible, or even thinkable. To believe otherwise would be to reaffirm these mediations, even while rejecting them in writing.

Of course, no-one can fully separate themselves from their background insofar as we can’t separate ourselves from our history. That is, until a free society is created in which we determine the essentials of our history, until history is made consciously.

But there is a process – for myself, I have nothing to do with people who play middle class roles ( except my sisters a bit, and even then I have very little to do with them). One can challenge one’s background, its roles and environment to a certain extent, move away and have virtually no connection with people whose complacency one finds disgusting and whose financial and existential security remains inextricably linked towards maintaining such a risk-free complacency. On a very simple basic level, one doesn’t have to go to their parties or hang out with them; one can explicitly critique the falsity of the friendship, or incite some form of subversion of this scene.

Likewise, those who ” said they were “coming around” to the insurrectionary position and to its consequences” could have been asked what they meant concretely by this – what practical decisions such an attitude had lead them to, what risks did they take. Which would have challenged that possible facade of politeness you talk about or, alternatively, revealed their supportive attitudes as genuine, that people were honestly confronting the sick mentality of this upper middle class milieu and not just saying things that would sound correct to you in order to appease any possible tension in your contact with them.

Two months on – and what’s the atmosphere in Baltimore? Any developments from the local state or the cops, or from liberal–lefty recuperators, the church etc.? Are the riots still a topic of conversation? Have the events in Charleston had reverberations in Baltimore?

best –

Sam

May 22, 2015

Is the author going to reply to the questions I asked?

May 23, 2015

http://ruinsofcapital.noblogs.org/rites-of-passage/

May 23, 2015

greek translation here..

http://gourmet-prolet.blogspot.gr/2015/05/blog-post_22.html

May 24, 2015

I like this a lot. One comment: According to your very persuasive argument, #blacklivesmatter is reactionary in the same sense as #alllivesmatter, i.e., it wants inclusion, and it seeks validation, approval, and legal recognition. It is not fighting words. It follows, then, that #nolivesmatter is also something quite important that you fail to mention: a statement of fact, an acknowledgment of reality. All proletarians live under threat of discard and annihilation.

March 15, 2018

Correction on footnote #2: 1) Lincoln did not send troops into Baltimore in Spring 1861. Ben Butler, commander of the MA troops attacked on April 19, did that; Lincoln was furious and relieved him of command (exiled him to Fortress Monroe in VA, where he took in escaped slaves, deeming them “contraband” and in so doing accelerated black agency in attaining their own freedom); 2) martial law was never declared in MD during the Civil War–no curfews, civilian courts remained open, though troops remained. See sources/period documents in Mitchell: Maryland Voices of the Civil War, Johns Hopkins Press, 2007.