The headlines are now so common that they’ve become banal, seeping into every aspect of our lives: from the office, where we’re told: “Wearable technology started by tracking your steps. Soon, it may allow your boss to track your performance”; To the warehouse: “If Workers Slack Off, the Wristband Will Know”; and finally back onto the streets: “Detroit is quietly using Facial Recognition to Make Arrests.” We are measured and tracked so thoroughly that it’s become habitual, each new privacy outrage seeming to fade away more quickly than the last. The body is a tally for capital. Every ad campaign will tell you that you are the irreducible individual, your body your own, your identity unique. But the reality is that you feel thoroughly paralyzed and increasingly faceless. Every ounce of creativity bled from your mind must be marketed, and every effort to improve your health renders basic rights over your body to faceless powers sitting behind every fitness app and phone camera.

For many, this is a clear case of what academics call “neoliberal subjectivity,” where recent changes in the form and function of capitalism have supposedly turned the body into a project to be managed and perfected by the atomized individual. Anyone making this argument would likely cite widespread data suggesting the consistent growth of the health and fitness industry in the United States over the years following the economic restructuring of the 1970s–this being the supposed era of “neoliberal” capitalism. From job growth of personal trainers and nutritionists outpacing the average, to a massive increase in new health clubs over the past decade, and a continued increase in dietary supplement consumption, private investment and growth in the industry is seen as a replacement for a previous era of government investment in public health. With the rise of fitness trackers and health apps, there are certainly more ways than ever to try and make calculations about the body, but to try and force this into the rote periodization parroted by so many academics is neither informative nor sufficient. The body has long been an economic subject to be counted, molded, and produced under a constantly expanding regime of bodily calculation. The features of this regime can take many forms, and the individual dimension is only one of many. Against this highly individualized approach there is the calculation of global and population level imperatives of body management, which put a premium on reducing obesity rates and increasing exercise as a way to improve public health outcomes and to reduce costs. We are invited to be healthy, with at least some relation to personal calculation, either for the good of society, or because we owe it to ourselves.

When viewed as a result of “neoliberalism,” the solution revolves around a rejection of calculation either by demanding the state take better care of our bodies through social services, or through movements such as body positivity and health at every size that reject calculation as the sum of a body’s worth. If any social problem is blamed on “neoliberalism” as a specific stage of capitalism, the implicit presumption is that capitalism itself may not be fundamental to the issue, and a solution can therefore be found without the necessity of any systemic change. It doesn’t really matter if this change is envisioned as the product of state action or a social movement. While the instincts behind such critiques are right and valuable, any consumer politics rejection of calculation or any appeal to the state for reforms simply means that capital will do the calculation for us. Our bodies don’t belong to us, and the types of bodies we have are largely made before we can act on them at all. This does not mean we cannot change, or craft our bodies, but we do so under conditions beyond our immediate reach. The dominant social myth today, however, is that our bodies are the last refuge of “the natural.” It’s just a matter of proper cultivation, allowing us to dig down to the vestiges of a primal body that’s somehow always with us. But the further we dig, the more likely we are to find no “natural” body at all. Even at its deepest levels, the body is a mesh of scars and habituated damage from a life of work, knit together with prostheses of plastic and metal, buoyed on a biome shaped as much by the chemical and micro-ecological conditions of our environment as by the macronutrients in our diet. All of this, of course, is then brutally reduced to the tabulation of a BMI score for use by some insurance company. The body is not and never was natural. Instead, it is one of the many hostages of capital, exhibiting the wear and tear of economic calculus. Capital not only shapes our environment, but also resides in our bodies, searching for value in our muscle fibers and adipose tissue. Epidemics of the body, from malnourishment to obesity, produce directives about what we can do, what we should do, as if we are responsible. As if the body itself is a debt already owed to the material community of capital.

When we think of the word regimen, we usually think of a way to order or control an individual, either self-imposed, or imposed by others. Medical regimens are historically the most popular. If the regimen were an object it would be that pill case divided up into seven neat slots with a letter stamped above each one to indicate a day of the week. Regimen comes from the latin word regere, meaning to rule, but is also related to regimentation and regime, which go beyond individual rule to collective rule.[i] Our bodies are stuck between a regimen and a regime, between our restricted life choices and our choices toward life that get restricted. We all have our own forms of diet or self-rule. Although the word diet today mostly denotes eating habits, it has always retained some of its older meaning: from the Greek word diaita, meaning a mode of living, which for the Greeks, extended to attitudes, behaviors, dress.[ii] Diet is the form that regimen takes, which is historically specific to different regimes. This is the first article in a two-part series about how diet, regimen, and regime are all present together in different periods of bodily calculation. This first piece offers one of many potential historical accounts of how we arrived in the bodies we inhabit today, particularly around what it means to be healthy.

Circulation

What a body is, and what it means, can largely be understood by what it is meant to do. As capitalism drove a factory-shaped wedge into pre-capitalist society, the body went through a series of shocks and changes. It was still the vessel that worked, that reproduced itself, consuming energy in order to expel energy, in need of rest, food and temperature regulation. But throughout this period, both what was needed of the body and what was known about it changed. Advances in anatomy and physiology created new frameworks for a healthy body, which was subsequently used as a metaphor for a healthy economy. Meanwhile, the body was cast into entirely new environments and made to suffer entirely new forms of pain on plantations, in factories, or buried in the new slums of early industrial cities. All of this, in turn, transformed the body itself.

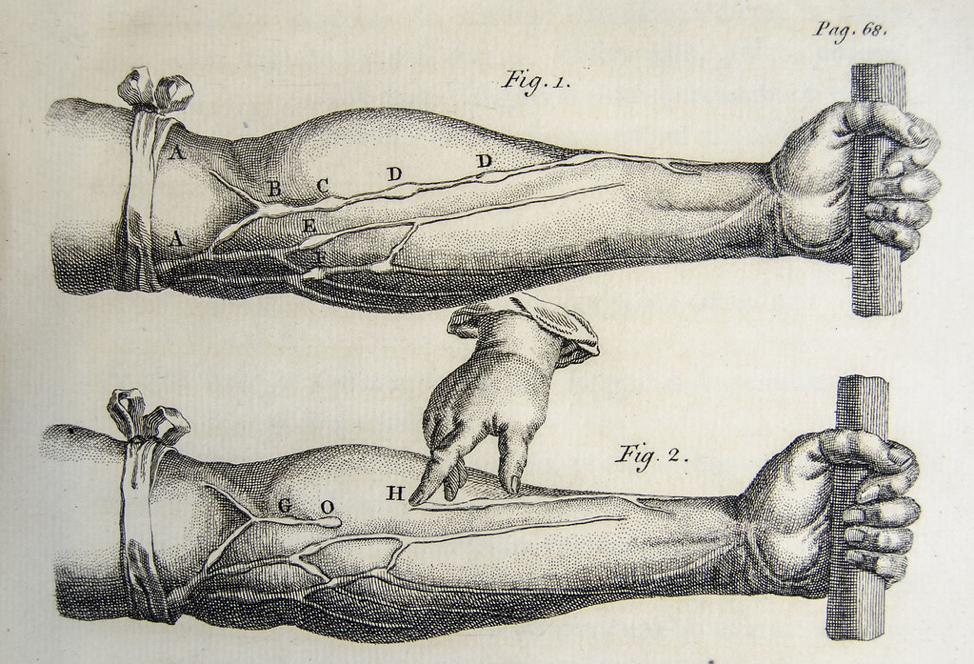

For the first half of the 17th century, body heat was thought to be the variable that determined differences in health, gender, and species. This view began to change with the publication of the anatomical text, De motu cordis, written by English physician William Harvey. When he wasn’t dissecting animals (both dead and alive) Harvey served as the physician to King James I and Sir Francis Bacon, the latter of whom he criticized for writing, “philosophy like a Lord Chancellor.” He was among the new generation of professionals who would ultimately ally with the interests of the old ruling class to create an “Enlightened” bourgeoisie and a modern, liberal-imperial state to host it. Among such scientists, there was little respect for old superstitions: Along with a group of military doctors, he was once ordered to give his medical opinion regarding the trial of seven women from Lancaster accused of being witches in 1634. Harvey and his group found “nothing unnatural nor anything like a teat or mark,” and all the women were acquitted.[iii]

Through the dissection of hearts from “fresh corpses”[iv], Harvey observed not only how the heart pumped blood throughout the body, but also how it continued to pump, even after being removed from the body. Against the beliefs of the ancient Athenian Pericles and the Greek physician Galen, Harvey argued that it was not the natural heat of the body that caused blood to circulate, but rather the speed of circulation that heated the blood. Harvey came to this conclusion in part by comparing the beats per minute of a freshly harvested bird heart with that of a human’s and noticing that the bird blood was hotter as a result of a faster beating heart. With the heart as the central pump, the properly functioning body circulated blood to all parts adequately, with each organ playing an equally important role. This lead Harvey and others to believe that an interruption or blocking of circulation was one of the main mechanisms for disease and ill health.

But while the new professionalized bourgeoisie might reject old superstitions, it was busy building new ones. After this view of circulation appears in the medical literature it surfaces as an economic metaphor justifying increased trade between newly arising urban centers and their rural counterparts. Where the physiocrats such as François Quesney saw the soil and agricultural production as the lifeblood of the economy, the new era of “political economists,” such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo, argued that the circulation of trade was like the blood pumping through a body, with the city as its mechanical heart. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith criticizes the British economy for being like “those unwholesome bodies in which some of the vital parts are overgrown,” fearing that this economic imbalance can lead to a “small stop in the great blood-vessel, which has been artificially swelled past its natural dimensions,” ultimately resulting in “convulsions, apoplexy, and death.”[v] What was healthy for the body was healthy for the economy, making the body a reference point for the naturalization of capitalism as a set of social relations. This neatly aligned diet, regimen, and regime into one seamless flow of biological life where the body was hermetically sealed, dissected, measured, and assessed for its optimal circulatory conditions. The dreamworld of Robinson Crusoe to which economists regularly defer, is not only a world of fabricated social isolation, but bodily isolation as well.

Our current understanding of an appropriate, healthy body doesn’t stray too far from these roots in political economy. Aside from the health issues associated with, although not necessarily caused by, a body mass index (BMI) in the obese range, the CDC focuses heavily on the economic consequences for the US healthcare system and government, even remarking on the association between a high BMI and missed days in the office. Further than just an economic resonance, our perception of bodies today is still tied to circulation. Whether from discourse on “globalization,” which pits the free circulation of commodities against the restricted circulation of bodies, or the moral indignation that arises when a fat person doesn’t buy two airplane seats, a body’s fitness is judged by its ability to move. The critiques of using BMI as a marker for obesity, as well as the relationship between body size and health, have been well argued elsewhere, primarily by the health at every size, fat acceptance, and intuitive eating communities, but less has been said about the relationship between bodies and economic activity. The debate should not only be about body size and health but why we feel compelled to defend our bodily choices as healthy in the first place–and specifically, healthy for whom? Healthy for what? Aside from the fickle moralisms that relate body fat to some sort of failure, there is also an insidious utilitarianism that sees fat as less productive for the economy. The fear of increasing healthcare costs makes individuals responsible for collective outcomes when they have no say in how the system is built or functions. It is important to critique obesity research in order to fully understand its relationship to health, but we also need to recognize that health does not need to be defended in order to validate body size, because “health” as it is discussed today has less to do with the ability to be happy, capable and comfortable in one’s own skin, or to contribute to some communal flourishing, and much more to do with the bidding of capital. Health today is inherently the health not of human beings, not of the species, not of the planet, but the health of nation and economy.

Alimentation

The violent upheaval of peasant life in the interests of capital accumulation resulted in rapid urbanization and industrialization across Britain and much of Western Europe in the 19th century. Someone, somewhere, has traced whatever physical ailment you currently have back to this urban transition, but it’s important not to fall into the common trap of the natural movement therapist or the barefoot runner. Instead of making blanket statements about urban or industrial life being inherently bad for our bodies or our health, we need to think of it as a dose-response relationship. Our bodies are slow adaptors, but when the adaptations are made they can be quite profound. Exposure to toxic chemicals, spending most of the day indoors away from sunlight, exhaustive, repetitive motion, poor nutrition and hygiene all destroy the bodies of workers because of the speed and the dose with which these conditions are imposed. Even toxicity is a category largely defined by dose, but under capital, all of these conditions are toxic because capital always seeks the largest dose in the shortest time. We can, in fact, adapt to these and many other conditions, but only if we have the capacity to determine the dose ourselves. Beyond this, we of course should be able to choose the basic trajectory of what we are even adapting to in the first place.

Rather than a simple cultural side issue, such body politics have always been central to the communist project. Marx speaks in detail about working conditions in England during the 19th century, at a time when conceptions of the body were rapidly changing. Not only does he commit massive portions of Capital to quotations from the Factory Reports, describing workers’ various sufferings under the industrial regime, but he also explores the larger shape of such adaptations across the population. When describing the lumpenproletariat, as part of the broader category of surplus population, Marx says that the worst off of the lumpen are “those unable to work, chiefly people who succumb to their incapacity for adaptation, an incapacity which results from the division of labor.”[vi] The imposition of this new division of labor not only divided people by class and skill, but also by their body’s ability to adapt to the brutal conditions of their new lives.

Ripping the body from rural life was such a shock to the system that the body began to wither and die. Marx documents these changes in chapter 10 of Capital Vol I, and cites a report by German chemist, Justus von Liebig, calculating the average height of new military recruits in European countries with mandatory conscription. In Saxony, for example, the average height of a new recruit in 1780 was 178cm, by 1867, this had dropped to 155cm. In France, roughly half of all conscripts were rejected for “deficient height or bodily weakness”, and in Prussia, “716 out of every 1000 conscripts were unfit for military service.”[vii] Later, in chapter 25, Engels adds a citation from the medical officer of health for Manchester who notes that the average age of death for the upper classes was 38, but for the working class, it was just 17.[viii] Factory work and the removal of people from direct access to means of reproduction was crippling, and the destruction of the body by capital needed to be dealt with. To do so, governments created the scientific study of alimentation (the provision of nourishment to the body) which tried to understand the most efficient combination of calories and nutrients needed for survival so that feeding the relative surplus population could be cost-effective. What is the most the body can endure before it breaks? This is the body’s regimen under the regime of capital.

Major developments in alimentation science began in England after the passage of the New Poor Law in 1834. In a utilitarian attempt to streamline the state’s services to the unemployed, the New Poor Law required everyone without employment to enter into workhouses, where they were to receive shelter, food, and temporary employment, instead of asking for money on the street. Registering at a workhouse also meant that men gave up their right to vote. Regulating food consumption in these workhouses served a dual function. Not only did the state save money by not feeding the poor “too much,” but it was also a way for the state to regulate hunger as an incentive to keep people in the workhouses motivated to work: “To avoid luring poor laborers away from paid employment, the New Poor Law instituted a ‘deterrent policy’ which stated that a workhouse should provide a subsistence level living at a standard lower than that of the lowest-paid worker in the area.”[ix] The role of alimentation science was to create an equation of food consumption, energy expenditure, and hunger to fit between the suffering of low wage labor and the suffering of unemployment.

Through experimentation on the unemployed and incarcerated, alimentation scientists, Dr. Thomas King Chambers and Edward Smith, identified adipose tissue, or body fat, as a mostly unnecessary and excessive part of the human body. Influenced by the work of Justus von Liebig, the same chemist Marx cites, Chambers and Smith argued that adipose tissue was stored food energy that was consumed in excess of the amount of energy a body expelled to function. Fat then quickly became a sign of overindulgence in energy and was found to have no place on the bodies of those in the workhouses, since the presence of adipose tissue was seen as proof of overfeeding. Adipose tissue became the physical and material base through which the state measured how effective and efficient it was at feeding the poor.

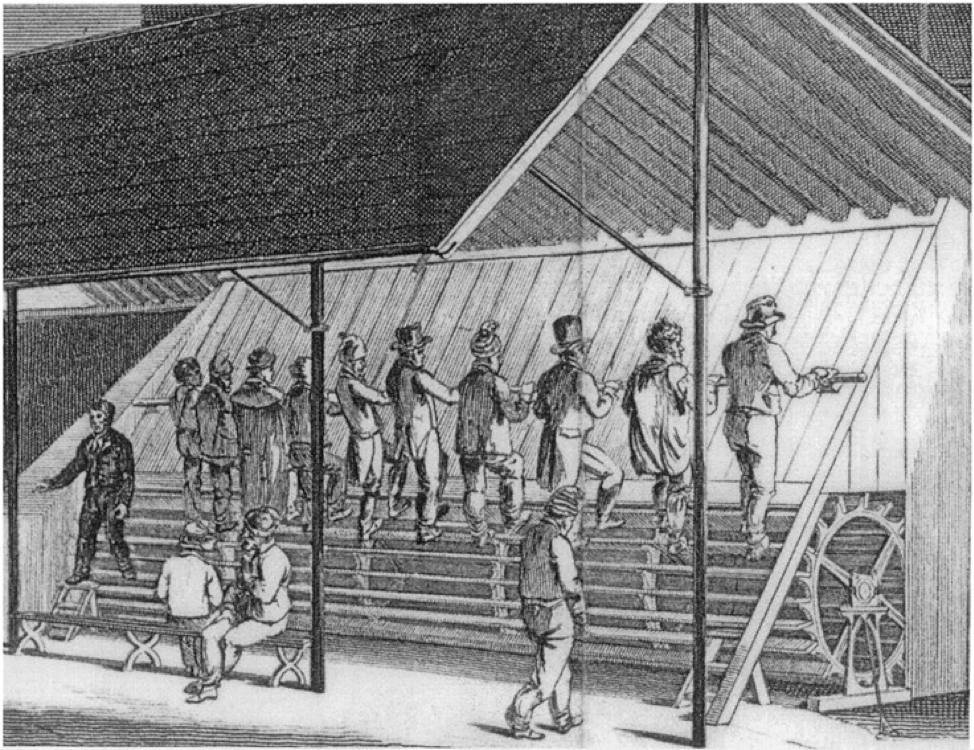

Much of Justus von Liebig’s physiological work was on muscle tissue, where he observed that protein, not carbohydrates or fat, was used to help muscles contract (determined by measuring the production and excretion of urea). From this observation, Liebig concluded that protein was the only necessary nutrient needed in a human diet, and that most health ailments could be cured through an increase in specifically animal protein in the diet.[x] Ever curious about the minimal needs of human survival, Edward Smith set out to test this theory on Scottish prisoners. But they weren’t just any prisoners. Instead, his study group was composed of prisoners who had been the first to be subject to a new form of subtle torture: the treadmill. Originally invented in 1818 as a human-powered corn mill, the treadmill was soon popularized as a torture device for prisoners, and by the mid-19th century over half the jails in England, Wales, and Scotland were equipped with the machines. Smith figured that if he measured the amount of urea excreted by prisoners on days they used the treadmill, and compared that with their rest days that there would be a significant difference due to all the extra muscle contractions while using the treadmill. To his surprise, there was no difference in urea excretion, suggesting that the energy source expended was not coming from protein.

Food restriction in workhouses was part of a larger movement that radically changed social views on body fat. For much of the Victorian period preceding the New Poor Law, body fat was seen as desirable since it represented wealth and the economic capacity to eat with few restrictions. While at first body fat became a way to stigmatize the poor, the association of fat with laziness and amoral excess soon made its way to the middle and upper classes as well. This occurs not only through the actual economic calculus of the state, but also through the proliferation of economic metaphors for the body and food consumption. For Chambers, “fat was considered a poor investment; it did not retain its worth in storage, but was only valued if its potential for combustion was realized.”[xi] In this sense, body fat is compared to uninvested capital, swimming around looking for a productive place to be invested but finding nowhere to go. Alimentation science was created as a way to balance the state budget on the backs of the poor, so it is fitting that much of the language used by Chambers and Smith to explain how the body stores and uses food energy would be framed in the language of transactions, investments, and sunk costs.

We find ourselves in a similar situation today. The disciplines of nutrition science, public health, and food science each have their roots in the alimentation science of the 19th century. Nutrition science and public health focus on providing nutrition recommendations on the basis of positive health outcomes at the population and individual level. In 2017, the CDC reported that approximately 71% of young people are not eligible to join the military either because they are overweight or obese, lack educational requirements, or have a criminal or drug abuse record. The military has responded with various NGOs such as Mission: Readiness urging the state to make stronger interventions against obesity for the sake of national security. Capital seeks profit wherever it is found, and our physiological necessity for food and some degree of medical attention offer many opportunities. The state only takes issue with this arrangement if bodies can no longer perform their duties as state subjects, but any action taken by the state to remedy this issue can only cut into private industry profits slightly, since the government relies on tax revenue from those same profits.

We are simultaneously exposed to hyper-palatable, calorie-dense foods, diet supplements, and advertisements that idealize certain bodies which adds a compounding social stigma to the potential health effects of those classified as overweight or obese. Meanwhile the state plays both sides, at once providing agricultural subsidies to those that produce the food, as well as creating multiple programs aimed to “fight” obesity through the National Institute of Food and Agriculture. It is then perfectly fitting that in many of the reports, the main reasons for fighting obesity are increased healthcare costs and decreased work productivity. There is no master plan for capitalism to keep us unhappy or sick or big or small, there is only the need to accumulate capital, which necessitates the use of our bodies to turn M into M’. But beyond this, we can recognize that capital itself has contradictory needs when taking into account the various dimensions of this process, and different fractions of capital have clearly different interests. The food, agriculture and pharmaceutical industries have clearly built up profitable value chains around unhealthiness. At the same time, companies generally profit best from healthy workers, so long as they don’t have to carry too many of the reproduction costs. Then, at the larger scale, the baseline conditions for accumulation must be continuously imposed and maintained (this is called “original accumulation”), and this often requires a relatively healthy population of state enforcers.

Meanwhile, all of this plays out in the realms of science and culture. Food scientists are still obsessed with protein, except this time their creative energies are put toward enhancing the amount of protein in everyday foods such as yogurt, pasta, and even water. Whey protein, a by-product in the production of cheese, is one of the most common forms of supplemental protein on the market today, with a projected industry value of $14.5 billion in the next five years. As both carbohydrates and fat are demonized by the popular press and diet gurus, it seems as if we have returned to the consensus that protein is the only “true nutrient.” It does not suffice to reject the importance of protein as if it were merely a product of corporate propaganda, nor does it make much sense to replace your next meal with a protein shake just because it’s supposed to be healthier. All of the different macronutrients, protein, fat, and carbohydrate play a valuable role in making our bodies function, and how much of each of them we need to consume is probably best oriented around what we want our bodies to do.

Corpulence

The mid 19th century also saw the rise of diet books which helped transform the bodily regimen of dieting from class-based punishment to social and moral requirement. One of the most prominent of the period, Letter on Corpulence, by William Banting, opens with, “Of all the parasites that affect humanity I do not know of, nor can imagine, any more distressing than that of Obesity.” The pamphlet reads like the historical equivalent of any other contemporary diet ebook in Calibri font, following the usual formula of walking the reader through the author’s weight struggles, why everything else failed, and arriving at a programmatic solution that has no downsides whatsoever. Banting was no stranger to the power of metaphor. He was heavily criticized for his description of obesity and body fat as a parasite, because many people took this description literally. Banting had to send out a public letter explaining himself and wrote a disclaimer in subsequent published editions clarifying that fat was not actually a parasite. This points to how strange this new relationship to fat really was. How could fat be draining the body of life and energy when it was in fact stored energy waiting to be used?

Banting’s pamphlet helped stigmatize fat for the middle and upper classes in two distinct ways. First, he positioned obesity as affecting all of humanity at a time when a large portion of England was either starved by the wage or starved by the state. Second, his solution to obesity was only attainable to the rich. For Banting, the cause of obesity was sugar and carbohydrates, which lead him to recommend a diet of mostly meat, some boiled vegetables, and, of course, an assortment of sherries and whiskeys. For anyone without a significant amount of disposable income, this diet would be impossible to sustain, positioning rich people as those with the unique means to access vibrant health. Foods accessible to the working class and those served in the workhouses such as bread, butter, and potatoes, were seen, much like the working class itself, as a problem. In many ways Letter on Corpulence is the anti-bread book. Fittingly, the best way to find a copy of the pamphlet today is on a number of low-carb diet websites that host Banting’s pamphlet to legitimize the false notion that carbohydrate intake is the main cause of fat gain and responsible for increased rates of obesity. In a fitting twist of fate, Banting’s legacy lives on in the spirit of the modern gym bro who says he’s keto but still slams beers with the boys.

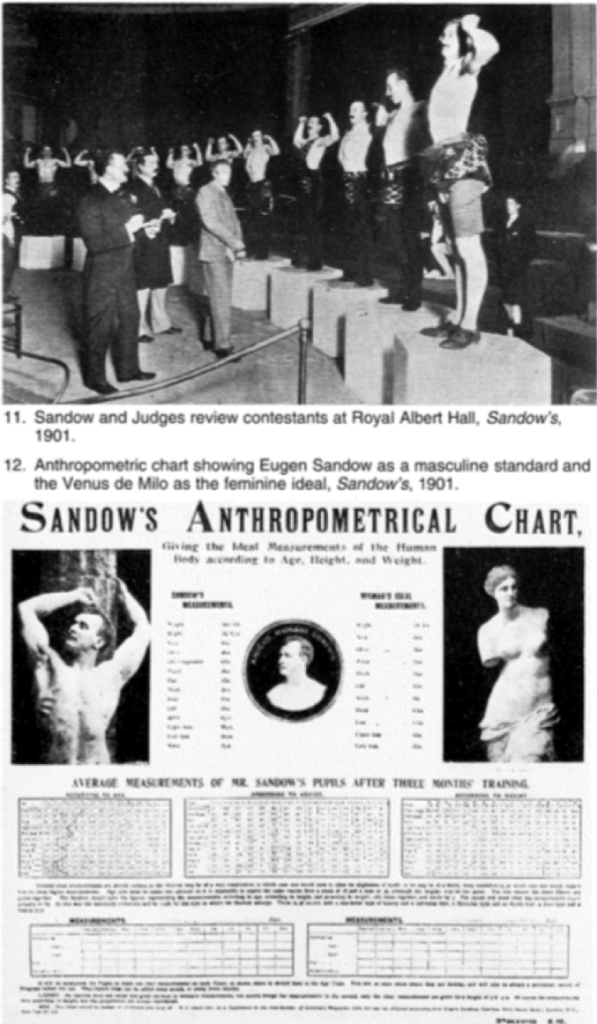

Middle and upper class obesity fears were also managed by the creation of health and diet pills. By 1855, advertising was going through its first modern boom due to decreasing costs of print production, and the abolition of the Advertisement Tax in the UK. Health and diet pills were some of the first products to be advertised en mass because early advertising was used for products people didn’t know they needed. All of this took place at a time when the body was at once becoming the subject of more scientific discoveries, as well as becoming more mediated through the new industries of photography and film. Advertising was only one dimension of this new mediation. It is out of this period (albeit more toward the end of the 19th century), that physical culture first gained a mass popularity. But its modern character was couched in classical allusions. One of the movement’s central figures, Eugen Sandow, originally a circus performer, began to pose for photographs where he imitated the style of Greek gods. By the 1880s, Sandow had created a health and fitness magazine, Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture, that outlined exercise routines and food regimens that would help people unlock their body’s full potential. Sandow also asked readers to submit progress photos of themselves demonstrating how their bodies had changed under Sandow’s regimen, which were then published in the magazine. Along with D.L Dowd, another physical culturist who used the same method to promote his book Physical Culture for School and Home, Sandow arguably posted the first ever #transformationtuesday. This practice of mediation helped solidify the body as a project that the middle and upper classes must work on.

Physical culture offered a critique of industrial society, arguing that industrialization was to blame for the striking gap between the chiseled bodies of Greek statues and the slowly shrinking and weakening bodies of the late 19th century. The tacit comparison here implied a civilization-scale degeneration: The pollution, machinery, and close quarters of the early industrial landscape were all said to be sucking the vitality out of human life itself. But the solutions did not share the same scope. Instead, remedies were more individual, including special exercise routines and a steady supply of liver tablets, the magic supplement of the era. The body becomes a battlefield that at once unifies a certain bodily experience and lays bare its divisions. This is but one manifestation of the material community of capital, since no one, despite their material advantage, can be completely protected from the consequences of their environment. But the liberal response is to pose a false equivalence, presuming that the opposite is also true, as if everyone, despite their class position, can take equal or at least sufficient measures to protect themselves from the damaging aspects of this new environment.

The contemporary version of this anti-industrial critique is the rise of the Paleo food movement and Crossfit. Such movements, whether past or present, know that something is wrong, but they can’t quite find the culprit. For followers of the Paleo diet, or other whole food and wellness-adjacent diets, the villain is “processed foods,” but the more you ask about it, the more the definition disappears. Is pasteurization a form of processing? Boiling? The holy act of juicing? All of these actions can change the nutritional content of food, but they say nothing about why our bodies are in pain. In 2015, Crossfit guru and physical therapist, Kelly Starrett started a non-profit called Stand Up Kids, which identified sitting as a major health risk for children. The goal was to bring the standing desk from the workplace to the classroom as a way to help combat childhood obesity, going far enough off the deep end to compare sitting with smoking. Rather than sitting for eight hours of school or work, the solution is just to do it standing. This is the kind of proposal that only looks like a solution to people who don’t actually have to stand up all the time at work. It addresses a real problem, which is that kids have less time for P.E and recess than before, but instead of offering the obvious solution of more recess (where kids can choose to sit or stand as they damn well please), it presumes the necessity of a labor-regime guided by productivity even in schooling. The result is a false solution that makes the entire situation even more unbearable. In the end, it all amounts to the politics of the biohack, an attempt to bring something natural or holistic into our manufactured world but without actually changing anything about that world itself: a strategy that is all diet, with no consideration for regimen or regime.

Insurance

Along with the state-led calculation of body fat for budgetary purposes, private industry also adopted a similar economic calculus of the body through the development of life insurance plans for middle and upper class families. Rapid urbanization made land access scarce, which shifted the measure of family wealth from farmable land to the wage. If the primary wage earner died unexpectedly, families could no longer rely on the land to reproduce themselves, causing severe economic hardship and, occasionally, outright starvation. Life insurance companies saw themselves as both a necessary boost to the productive economy, as well as a noble social service. To calculate the likelihood of a person’s death for the sake of ensuring uninterrupted consumption is the regime of capital regimenting the body. Where there was once a family farm, there was now a lump sum of cash. However, this industry would only be as profitable as the accuracy of its calculations, so, how much is a life worth?

The simple goal of a life insurance broker is to make an educated guess about how long you have left to live and how much your life is worth. Based on a variety of factors, some health related, others related to family wealth and occupation, this educated guess turns into a price that the policyholder pays at some regular interval, which is related to both how much the life insurance company will pay out at the time of death, and also how risky that life is to insure. The life insurance industry began to develop in the US and Europe in the 19th century, but with slightly different characteristics. In Europe, primarily in England, the history of alimentation science and the New Poor Laws meant that the life insurance industry was quick to hire physicians and alimentation scientists to add health as a measure in their life expectancy equations. In fact, his work on energy expenditure and caloric needs in the workhouses helped earn Dr. Thomas King Chambers a job with Hand-in-Hand Insurance Company in 1850.[xii] While physical well-being was not absent from the life insurance industry in the United States, it took a much less scientific form in its early development. For most of the 19th century, physical examinations were routinely performed by board members of the life insurance companies themselves, though they rarely had medical experience. In many cases the exams consisted of making sure the client was not currently drunk at the time of their application, with tests such as standing on one leg for five minutes, or being able to jump over a table.[xiii] It was only toward the start of the 20th century that medical doctors were employed by US life insurance companies to do client examinations, and it was around this time that body fat began to play a role in determining the price of a policy.

Life insurance companies profit by making really good educated guesses. In order to measure how good they are at guessing, they compare the amount of recorded deaths per year of policyholders with the amount of deaths they expected from their calculations. In places where there is a significant discrepancy between actual deaths and expected deaths, the companies do further research to understand why. By 1913, the association of life insurance medical directors and the actuarial society of America published a report citing body weight as being associated with the gap between expected and actual deaths since 1885.[xiv] At the time, the relationship was not very strong, but this initial work in the life insurance industry set the stage for broader social concerns about obesity that arose after WWII. One of the more interesting and alarming results to come out of this study was not necessarily the relationship between body weight and life expectancy, but between marriage status and life expectancy for women: “Mortality among married women was about 50% greater than among spinsters, and it would therefore be quite possible to have a lower mortality among a group of spinsters greatly overweight than among a group of married women of average weight.”[xv] Statistician and vice-president of Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, Louis Dublin, used this information to create standards for a “normal” relationship between age, height, and weight for both men and women, solely based off their likelihood of death.

Much of the work to find “normal” body weight measures done by statisticians like Dublin followed the earlier work of astronomer and mathematician, Adolphe Quetelet. Quetelet is most well-known for creating the Quetelet index in 1832, which applied the statistical concept of normal distribution to the human body, providing a way to measure the relationship between height and weight. This index was eventually adopted by obesity researcher Ancel Keys in the 1970s and renamed the Body Mass Index, or BMI.[xvi] A normal distribution looks like a bell curve on a graph and can be used to identify broadly common features of a certain population or data set. All the values on the X-axis of the graph that fall under the hood of the curve (usually within 2 standard deviations, which includes 95% of the data in a perfectly normal distribution) are considered normal, and the thin tails at the edges (composing about 5%) of the graph demonstrate exception. By conducting multiple population-level studies of people’s height and weight, Quetelet was able to create a mathematical formula (weight / height^2) for determining the “normal” weight range for any given height, the same formula used in the BMI.

But what is normal? It’s important to recognize both the underlying mathematical distribution being referenced (rather than presuming social “normality”), and also to be critical of how that distribution itself was derived. Why can some seek shelter under the hood of the normal distribution while others are squeezed between the tail and the X-axis? The division between 95% and 5% (within or beyond two standard deviations, respectively) is itself fundamentally arbitrary. More damningly, Quetelet’s population studies were both done in Belgium, so the majority of the subjects were white europeans. This was not, then, an adequate sample of the human population. But the measure itself is even questionable, because of its attempt to derive data about “mass” secondhand, with no attention to composition. BMI doesn’t accurately take muscle tissue into consideration, since it only calculates height and weight. This inaccuracy is amplified when BMI is used as a proxy for adipose tissue (as it often is). To be fair, Quetelet never meant for his index to be used as a way to measure obesity or health, he was interested in the applicability of physics, math, and science to human populations. But by identifying the various characteristics of the “normal man,” Quetelet hoped that human behavior could be better understood, predicted, and governed. Meanwhile, Louis Dublin and the insurance companies were only interested in normality to the extent that they could use body weight to accurately calculate life expectancy. It is the combination of Quetelet and Dublin that produces the BMI regimen, a wedding of statistical discovery and the calculus of capital.

Francis Galton, the founder of eugenics and cousin of Charles Darwin, was fascinated by both the physical culture of Sandow and Quetelet’s “normal man.” While Sandow wanted to develop methods for physical development that could help anyone achieve their own potential, Galton saw a method for isolating those with the best genetics. But best is always contingent. In the case of Sandow and physical culture, the ideal body was quite literally modeled after statues of the Greek gods, with Sandow frequently photographed in a toga, striking statue-esque poses. As one of the founders of modern bodybuilding, Sandow created judging criteria for bodybuilding contestants by measuring the muscle size and limb length of the pillaged Greek statues on display in the Museum of London.[xvii]

But what Galton saw in physical culture was a way to test genetic superiority rather than a democratic process of personal development. The eugenicist assumed that those with the best genetics would naturally be strong and fit without training, which positioned physical culture as a form of athletic talent selection to identify those at the furthest right edge of the bell curve for strength and muscular hypertrophy. Here the interest in the normal curve was inverted, as Galton specifically sought outliers. Galton was also interested in Quetelet’s index, then, but only in relation to the life calculations of insurance companies, what he called “the actuarial side of hereditary,” searching under the hood of the normal distribution for optimal life expectancy. Meanwhile, eugenics and physical culture shared an interest in the nation state, both hoping to harness the body as a way to create a strong nation, albeit with different philosophies as to how this should be done. Regardless, participants of both movements readily helped train their country’s soldiers for World War One.

It’s not uncommon for bodybuilders to think of themselves as artists or sculptors, “uncovering” what lies within through training and diet. The regimen of physical culture faces the past as much as it does the future. On the one hand there is a nostalgia for the force and power of pre-industrial bodies, only used for their “natural” purposes. On the other, practitioners approach such questions with a utilitarian rationality that despises the wasted potential of bodies left underdeveloped. Throughout, the language of entrepreneurialism tends to dominate: Sandow “discovered” the exercise routines that he sold through his magazine, he was an engineer and inventor as much as he was a jacked renaissance faire performer. This is one form of the bodily regimen derived from the late 19th and early 20th century. It is effective because it harnesses the desires of bodies constantly forced to endure a hostile world. It does not merely offer two different aspirational escape routes (one to the past and one to the future), but it combines them, appearing to be the best of both worlds.

The scientific application of calculating the body through diet and exercise was positioned as the only way to return to a pre-industrial body, a body full of strength and vitality, unencumbered from the toil of wage labor and putrid urban living conditions. Although this orientation toward science and nature is shared by the eugenics and physical culture movements, they are not essentially bound. Unlike eugenics, physical culture can exist without an origin story or essential genetic qualities. Modern bodybuilders look nothing like old Greek statues, with many all too aware that judging criteria can feel as arbitrary and subjective as a dog show, or the Oscars. One of the positive influences of anabolic, androgenic steroids (AAS) on the bodybuilding community since the mid 20th century has been to fashion an aesthetics away from a romantic past and toward a freaky, experimental future.[xviii]

Calculation

It is again through insurance and healthcare that health crises are wrongly boiled down to neoliberalism, or the state retreating from its public health duty. To accumulate, capital must calculate, leaving a wake of visible and invisible scars on proletarian bodies. Rather than seeing the dystopian use of health trackers and private data as practices that should or would have been prohibited by a strong state (if it weren’t for that pesky neoliberal turn), they can be seen as building upon a long history of bodies that have already been calculated. While the tech sector today is vastly different than the industrial sector of the 19th century, one thing they share is the ability to attract investment. That many today’s tools for bodily calculation come from the sector that capitalists believe will save the economy should be no surprise.

Our capacity to change our bodies is both present and impeded, with our bodies constantly being modified by the choices we make and the choices made for us. The only way through this mess is a rejection of health as it has been defined for us and against us. But a new understanding of health need not be a rejection of bodily calculation in favor of some fake-primeval “holistic” bullshit. To survive today’s hellworld and pass through it to the possibility of a better tomorrow, we need to be able to know if the dose is toxic. The case of the BMI measurement is an illustrative example. Knowing the history of BMI, it’s clear that using it as the single measure of bodily health is both bad science and harmful—it plays essentially the same role that GDP does for economics. Nonetheless, the fact remains that insurance companies were able to use it as one of many measures that helped them predict life expectancy with a decent degree of accuracy. The chain of causality, however, falls short. The biggest and perhaps most common error made here is to assume that a higher body mass index alone is what is causing shorter life expectancy, rather than a host of other factors that are, in fact, intentionally not calculated. These are factors such as poverty, racism, lack of social support, lack of access to medical care, or occupational, and mental health. BMI seems to have a degree of predictive power when it comes to life expectancy, but not as much explanatory power, especially if this host of other life factors are considered. The point, then, is not to reject any form of calculation as inherently oppressive, but to perceive the power relations that structure the activity and to ask ourselves if an oppositional use of calculation is possible. In figuring out what health and strength mean, and how to build them, one of the most important things to do is, in fact, to push for greater calculation—specifically, for the inclusion of all these factors that go uncounted. Only with these other things in mind can we choose if or how BMI has an impact on what we do with our bodies.

The exact ways that we measure and the variables we use are much less important than what we are using it for. We must do so with the understanding that failure is as likely as success, and that the successes we do have may arise in unexpected places. The physical culturists of the late 19th century sold a bunch of bullshit supplements and used the arbitrary measures of Greek statues to guide how they developed their bodies, but despite all their missteps, they still got jacked. Against the assumption that calculation saps the vitality out of life itself, it is precisely this calculation, however maladroit, that gave physical culturists the base of their critique of industrial society. This critique framed how and why they used their bodies, it gave them a life. If we can better understand why and how we calculate, we can move away from calculation being something inherently done to us from above, and toward a way of interpreting and guiding our own bodily practice—in other words, toward forms of counter-calculation that can be deployed against the world as it currently exists.

On top of not having full control of our bodies, we also don’t have control over our historical conditions. It was not their practices of calculation that killed the early physical culturists, nor was it their ideological failings, it was instead an entirely different type of imperial calculus conducted at a horrifying scale beyond their immediate control: World War One. Months before their bodies piled up in the trenches, riddled with bullets from a mounted machine gun, or decomposing from toxic gas exposure, they were building their bodies to defend their nation, wondering if their commanding officer would let them bring along the liver tablets they ordered through Sandow’s magazine. It’s easy to overvalue the importance of our own bodies, especially in the face of catastrophic climate change, ecosystem collapse, and civil war. For some, the focus on the body is used as an explicit retreat from the realities of the world around us. Yet it also cannot be ignored, everything we do in this world we do through our bodies. We should use our bodies for experimentation of all sorts, not as a way to prefigure the future, but a way to experience ourselves now. It is through this experimentation that we discover what we want our bodies to do, and it is from that intention that we can begin to build our bodies together.

–Kyle Kubler

[i] Brian Turner, The Body & Society Third Edition, Sage, 2008, p. 142

[ii] Ibid., p. 152

[iii] H. A. Clowes, “Harvey and the Lancashire Witches,” The British Medical Journal, volume 2, 1926, p.544

[iv] Richard Sennett, Flesh and Stone, W. W. Norton & Company, 1994, p.258

[v] Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1982, Penguin Classics, p. 604-605

[vi] Karl Marx, Capital Volume I, Penguin Classics, 1976, p.797

[vii] Ibid., p. 349

[viii] Ibid., p.795

[ix] Joyce Huff, “Corporeal Economies: Work and Waste in Nineteenth-Century Constructions of Alimentation,” in Cultures of the Abdomen: Diet, Digestion, and Fat in the Modern World, Palgrave MacMillan, 2005, p. 34

[x] Carpenter, Kenneth J. “A Short History of Nutritional Science: Part 1 (1785–1885).” The Journal of Nutrition 133, no. 3, 2003, p. 638–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/133.3.638.

[xi] Ibid., p. 43

[xii] Huff, “Corporeal Economies,” 2005.

[xiii] Terence O’Donnell, History of Life Insurance, American Conservation Co., 1936.

[xiv] The Association of Life Insurance Medical Directors and The Actuarial Society of America, “Medio-actuarial Mortality Investigation,” reprinted in Obesity Research vol 3, No. 1, 1995, p. 100-106.

[xv] Ibid., p. 106

[xvi] Keys, Ancel, Flaminio Fidanza, Martti J. Karvonen, Noburu Kimura, and Henry L. Taylor. “Indices of Relative Weight and Obesity.” International Journal of Epidemiology 43, no. 3, 2014 p. 655–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu058.

[xvii] Greek statues were also influential in the history of orthodonture, using jaw line measurements of statues to determine the category of the “perfect smile”. See Collins, Margaret. “The Eye of the Beholder: Face Recognition and Perception.” Seminars in Orthodontics, An Overview of Facial Attractiveness for Orthodontists, 18, no. 3, 2012, p. 229–34. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sodo.2012.04.009.

[xviii] It should be noted that this freaky future is not embraced by everyone in the bodybuilding community. There are also members that compete in classic physique divisions that seek to recreate the look from the “golden age” of bodybuilding in the 60s-70s.

December 12, 2019

interesting read