Imperium

The empire had fallen long before it collapsed. Corrupt elites ruled from a distance. Industry fragmented in slow motion, plundered by the rich and slowly pieced apart by foreign competition. For common people, the possibility of any sort of stable life slowly faded. The future itself seemed to recede into an impenetrable darkness, thick with the sound of some as-yet-unseen chaos slouching toward the present. The gap between the dim light of everyday life and that rapidly approaching night was filled with bone-deep madness. Tradition rotted from the inside out. Opiates muted the misery of ever-expanding unemployment and unrest bloomed in its thousand forms. Religious sects arose across the heartland. On the coasts, overburdened, underfunded cities sprawled outward even as their cores were flooded with unprecedented wealth. Slums spiraled in a fractal pattern around glittering ports. Foreign powers pressed inward from a distance, the military overextended and inefficient. Weaker armies fought asymmetrical wars against the empire at its edges. Corrupt officials were assassinated in broad daylight. Militias grew in the rural areas, filled with young, futureless men hoping to push out the foreigners and make a great nation strong once again.

In a way, this story describes every era of imperial decline, or maybe just the general environment of pervasive social collapse. In its specifics, it of course bears a remarkable resemblance to the current conditions of the United States—or maybe, at least, the conditions widely assumed to be impending. There is a truth to this resemblance, certainly. But the picture above is not an illustration of Trump’s America. It is instead a snapshot of the late Qing dynasty in the century following the Opium Wars, when the world’s strongest empire found itself roundly unseated from the helm of global power. Defeat at the hands of “inferior” foreigners, paired with rampant opiate addiction, political corruption and generations of growing economic inequality combined to define the era as one of “national humiliation.”

According to late imperial and early Republican reformers, the very “marrow of the nation” had grown weak. This first drive to Make the Qing Great Again therefore came in an overtly martial form. The military had fragmented after the Opium Wars and subsequent Taiping Rebellion, its capacities distributed out to local elites tasked with suppressing new uprisings or sent to keep the peace at the border. One result of this was the proliferation of martial sects and private armies. Some were funded by the local gentry, others emerged out of community defense and crop-watching organizations, and many found themselves in league with religious cults. These sects absorbed angry and unemployed young men seeking some alternative to a life of manual labor followed by drug addiction. Their program was simultaneously one of self-help and national rejuvenation. By making themselves physically strong and fanatically upholding symbols of tradition, these young men sought to restore the strength of the nation from the bottom up. In their view, moral rectification would help to ignite a new period of social rejuvenation, which would begin with a widespread rising-up of the population against symbols of weakness, decadence and foreign influence. Decades later, such themes would become common on the right wing of Chinese politics, systematized by fascist factions within the Nationalist Party such as the Blue Shirts and CC Clique and given a mass character in the New Life Movement of the Nanjing decade, which sought to restore the nation’s moribund “national spirit” via torchlight marches and mass imprisonment.

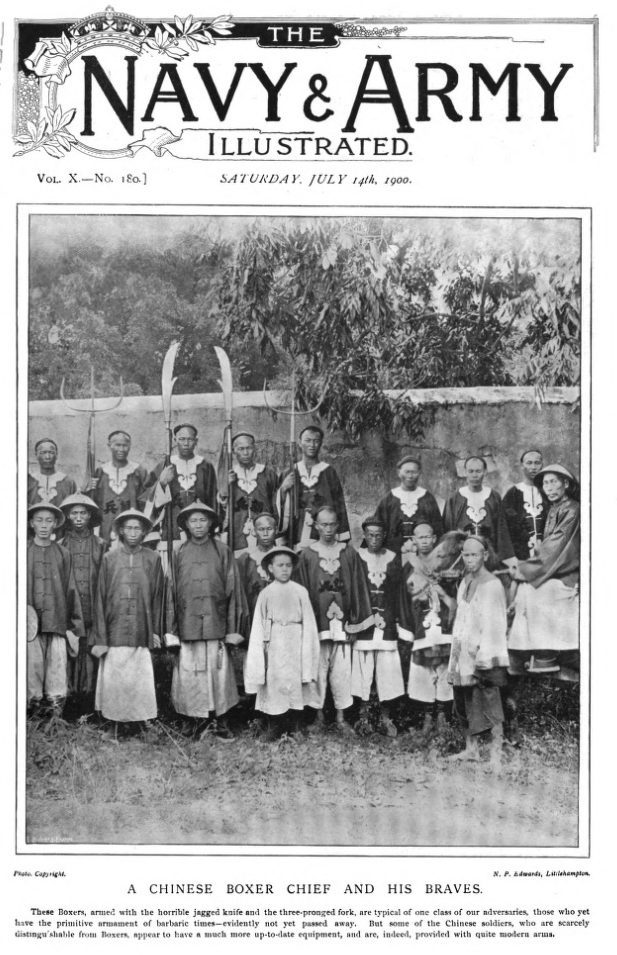

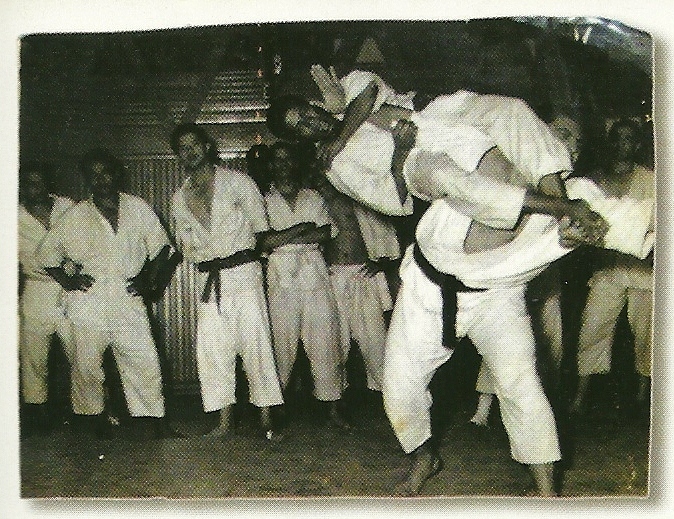

One of the few contemporary photographs purporting to show “boxers,” here printed in a military magazine SOURCE: Ben Judkins (https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2017/04/10/how-did-chinas-boxers-become-the-boxers/)

But all of the features of this native fascism began their slow, inchoate gestation within the late imperial system. If there was any one moment when all of these elements could be said to have first combined in the modern era, it would have been in what has come to be called the “Boxer Rebellion” in English. This name, however, is in many ways a misnomer. The martial qualities of the “rebellion,” for instance, were always in thrall to a folk-religious revivalism defined by things such as spirit possession and invulnerability rituals. At the local level, interest in martial arts grew alongside social and ecological collapse in the years following the Opium Wars. Whereas martial artists had once been associated with itinerant banditry and gambling dens, the renewed need for local self-defense groups and crop-watching organizations again returned martial practice to the community.[1] While certainly still locally relevant, martial skills were also increasingly obsolete in large-scale battle, and by the late Qing even many bandit groups were carrying rudimentary firearms. Martial practice therefore became alloyed with superstitious supplements designed to even out the asymmetries of increasingly mechanical warfare. The newly-popularized arts thereby took on more and more features of popular culture—particularly myths, rituals and other practices drawn from the folk opera, which served as most peasants’ primary interface with official narratives of national identity. This “revival” of the supposedly “ancient” arts was therefore just as much a reinvention, speaking to the new priorities of an Empire faced with increasingly dangerous competition from Western “barbarians” abroad and powerful rebel sects domestically. Fused with strains of Taoism, folk religious practice and Neo-Confucian metaphysics, the mythic role of the martial artist ballooned well beyond the practical.

Meanwhile, the “rebellion” was not an uprising against the government, but instead a spirited defense of it. At the time, the Qing state allied with the “rebels” against the foreigners, whose motto was “Support the Qing, destroy the Foreign.” It was only after defeat by international forces that the state, in an attempt to save face, redefined the movement as an anti-government “rebellion.”[2] Thus, the event is better understood as a novel upwelling of traditionalist fanaticism that grew within popular culture during a period of “national humiliation.” It is notable insofar as it prefigures many themes of later rebellions, but the state’s official relationship to the movement was one of tacit support followed by pragmatic disavowal, not unlike the relationship between the Trump administration and the far right today.

The Boxer Rebellion was most significant, then, not as an aborted renaissance but instead as a largely negative reference-point for future reformers and revolutionaries. In both political and cultural terms, it represented the epitome of naïve traditionalism in the face of a changed world. At the same time, as one moment in a long string of popular movements stretching back to the Taiping Rebellion, it also signaled the growing readiness of the populace for revolutionary change. The Boxers are significant because for both the right and left wings of 20th century Chinese politics, they represented the premature ascent of a new nationalism. For the far-right, this was a foundation to be built upon. Fascist theorists like Dai Jitao, Chen Guofu and Chen Lifu would later advocate that martial practice be reconstructed, made practical and fused with a modern nationalist-military philosophy (much like what would take place in Japan over the same period).[3] This would rejuvenate the “eternal spirit” of the nation through a ritualized, hierarchical performance of moral and physical cultivation.

For the far left, the Boxers foreboded the threat of an inelegant traditionalism that sought to reject reinvention and reform outright, guaranteeing cultural stagnation and the support of decrepit social classes. Nonetheless, the left also saw the potential offered by the Boxers’ mass base, many of their adherents evincing a popular desire for regimens of self-discipline and the construction of a power capable of resisting foreign encroachment. When the left began its own ascent, first in the form of one of the world’s largest anarchist movements and, later, in the form of the Chinese Communist Party, it also embraced physical culture and the martial arts. Much of the movement’s growth, after all, was to be found in its ability to build strength among those who had previously been powerless. The rise of martial culture was an important part of this, with Chinese anarchists and communists often actively recruiting from bandit groups, secret societies and local martial arts clubs. They diverged with the right, however, in their perception of physical culture as a tool in the strengthening not only of the “nation” but of the global proletariat as it built toward world revolution.

The Barbarians

While the immediate relevance of the Boxers might be clearest for those who inherited its results, their history also offers a more general lesson in the relationship between physical culture and political dynamics. In the years following the last crisis, the US has seen a rapid resurgence of the far right, including the growth of a new, wide-ranging militia movement and the founding of smaller religious-martial cults that bear no small resemblance to those of the Boxer era. These movements tend to enshrine combative and “tactical” aesthetics in a way that combines a bare minimum of combat training with a much more substantial perfomative reverence of sheer, gun-oil masculinity. Like the Boxers, their martial activities can only be understood as the ancillary of a much larger, quasi-religious physical culture that has found its base most readily in the very areas most abandoned by the distant machinations of that grim demiurge we call “the economy.”

This new era of physical culture has today fully permeated the increasingly dark, gritty and apocalyptic horizon of popular culture in general. On the one hand, we see lean, wild-eyed Americans sifting through the ruins of worlds destroyed in vague and terrible ways, dependent for their survival on the bare minimum of luck and martial force. The new world is defined by sudden gunfire from unseen locations, close combat with biker gangs and rotting corpses. On the other hand are the superhero blockbusters, the “great fascist opera of our time.” Infinitely accreting masses of criminals are swept away with a martial might so massive it reduces combat itself to nothing more than the image of sweat-greased fists punching forever through a glistening confetti that is, we are told, The Enemy.

Meanwhile, popular martial arts tournaments such as the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) have grown rapidly from no-rules grey market fight clubs, outlawed in most states, to some of the most-watched Pay-Per-View events in broadcasting history. The ascent of the UFC was accompanied by a widespread cultural awareness of martial arts—here advertised as “real” forms of combat, in contrast with the flowery, cinematic unreality of the Kung Fu genre—and by a massive increase in the number of people who began to seek combat training of one sort or another. The result is a situation that in many ways resembles the later 19th century more than the 20th: any random person on the street is more likely to have some level of training in hand-to-hand combat than would have been common in previous generations.

Like many things, it’s a matter of geography. The growth of the far right has been strongest in the American hinterland, particularly in rural areas that hardly benefited from the financial boom of the Bush Years, suffered inordinately during the economic crisis, and then found themselves excluded from the “recovery.”[4] These are areas like Josephine County, OR, where budget shortfalls are so severe that the Sheriff’s office can’t offer emergency services beyond limited hours and areas, the Sheriff himself suggesting that those at risk of domestic violence simply relocate to better-funded counties. In response, the local Oath Keepers (now known as the “Citizen Patriots of Josephine County”) moved in the fill the gap, offering their militia in place of the police, running emergency-preparedness classes and engaging in a number of minor electoral campaigns and community outreach projects.

The Oath Keepers in Josephine and elsewhere, recruiting primarily from veterans and former first-responders, are one umbrella organization within a much wider “Patriot Movement,” designating the new militias and their related organizations. Though increasingly associated with the “Alt Right,” the Patriots precede the neologism by several years and tend to wield a membership and organizational capacity far beyond what is common among other groups that fall under the label. The movement itself is internally diverse, fusing traditional libertarianism with remnants from the old militia movement of the 1990s and new Islamophobic organizations. It operates on an “inside-outside” organizing model, engaging in both formal grassroots electoral campaigns (largely attempts to enter local government or elect minor representatives into the Republican Party) and extra-state organizing via militias and community outreach organizations. Much of the overt white supremacy found in the militia movements of previous decades has here been shed in favor of an emphasis on class conflict with “globalist” elites in coastal cities, combined with open, militaristic Islamophobia and a toned-down, veiled racism toward the more diverse underclass of urban areas, who are seen as being in league with the elites via the patronage mechanisms of the democratic party apparatus.

A group of Oath Keepers in Josephine County during the Sugar Pine Mine conflict. Photo by Shawn Records for VICE. SOURCE: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/exq8en/miner-threat-0000747-v22n9

Patriot groups grew with remarkable speed in the Obama years, vastly outpacing the more traditional white supremacist organizations like the KKK and, by all evidence, still far outnumbering any one of the major factions within the “Alt Right.” According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, the movement grew from a mere 129 Patriot groups in 2008 to 1,274 in 2011 (compared to 334 non-Patriot militia organizations and a total number of 1,018 hate groups identified in the same year). Meanwhile, prominent armed standoffs between Patriot organizations and the federal government (namely the Bureau of Land Management) at the Bundy Ranch in 2014 and on the Malheur Wildlife Refuge in 2016 helped to launch the movement into the mainstream. At its height, the broadly-defined movement, including its religious offshoots (such as the Bundy family’s far-right Mormonism) had an active national membership somewhere in the thousands, with a nominal or secondary “supporter” membership in the tens of thousands, all amplified through extensive social media outreach.[5] Militia movements such as this have tended to peak under Democratic presidencies, and while the growth of Patriot groups has predictably stalled under the Trump administration, it has also become more institutionalized, with Patriot politicians elected to office and bills to devolve control of federal lands to local governments introduced to Congress.

Though the Patriots glory in their “tactical” aesthetic, even sending recruits to border patrols where they can learn basic military procedures, they are in many ways simply an umbrella organization of weekend-warrior types, often drawn from wealthier commuter-exurbs. In most cases, their calls to defend “freedom” and the “people” against the tyranny of the federal government are in reality actions undertaken to protect the Carhartt Dynasty of local landowners and industrialists in slightly-further-out rural areas across the American West. Though they do outreach and some recruitment among the rural poor, their actions very rarely defend the interests of those at the bottom of class hierarchies in the countryside—support for migrant workers is notably absent, of course, but there is also effectively no central material support for the poorest white ruralites either. All of their major campaigns have been aimed at protecting the rights of landholders and petty capitalists from onerous rents charged by the state. Insofar as they are able to recruit from the white underclass, these recruits are then employed in the service of local elites who themselves are often thrown into opposition against the “globalist” elites of the cities. The militias, at their most effective, have merely acted as a particularly aggressive arm of certain factions within the capitalist class.

Though they enshrine certain military ideals, physical culture plays a less obvious role in the Patriots’ day to day practice. In contrast, other resurgent far-right groups have taken physical culture as their foundation. The most prominent is likely the Wolves of Vinland, a neopagan tribalist cult, organized like a biker gang and based around a land project they call “Ulfheim” near Lynchburg, Virginia, where they crowdfunded the construction of a traditional Viking longhouse. Much smaller than the Patriots, the Wolves have three major chapters, with organizational centers in Virginia, the Mountain States and the Pacific Northwest, as well as a larger propaganda wing called “Operation Werewolf” that yokes together the participation of smaller groups nationwide. Much of their material is distinguished by a well-designed subcultural aesthetic, with clean logos plastered on professional-looking photos of muscle-strapped white men standing near fires, their faces painted with runes and shoulders covered by animal pelts, all accompanied by terse taglines well-suited to distribution over social media.

Jack Donovan and another member of the Wolves of Vinland, unironically hardstyling beneath thick tendrils of white dreadlock.

Aside from this aesthetic, however, the Wolves have made physical culture into a sort of foundation for their day to day practice, helping to attract new recruits. They promote entry into local gyms, regularly hold MMA-style bouts of hand to hand combat at their meetings and gain attention through contact with prominent figureheads in weightlifting and martial arts circles. Jack Donovan, the head of the Wolves’ Pacific Northwest chapter, made headlines for the group through his affiliation with a well-known powerlifting gym in the Portland area,[6] speaking on the owner’s popular podcast and taking instagram photos with Fight Club author Chuck Palahniuk. In the broader sense, Donovan’s main talking points on masculinity and “becoming a barbarian” are drawn from an entire cultural current that extends far beyond the Wolves themselves, embodied in everything from Alex Jones’ conspiracy theories to Joe Rogan’s popular podcast advertising athletic wear and nutritional supplements—equal parts flamboyant, “alt-right” fascism, as popularized by internet troll celebrities, and homegrown cornbred-and-militia white nationalism. And this current is not limited to the US, either. Donovan has travelled to speak at far right events in Europe, where appeals to “tribal” or “indigenous” identity form an essential part of local nationalisms. Meanwhile, in Italy, the rightwing comedian Beppe Grillo, leader of the populist Five Stars Movement praised the election of Trump in similar terms as Donovan: “It is those who dare, the obstinate, the barbarians who will take the world forward. We are the barbarians!”

Trump Country

Looking outward from the wealthy coastal cities, the average liberal also sees little more than growing barbarity. Culture appears to have atrophied, replaced by thinly-veiled bigotry, people “clinging to guns and religion.” Faced with a rising tide of terror across the global hinterland, the ever-civil urbanite seeks to simply reinforce the walls of the palace—maybe also applying for a grant to paint an anti-wall mural on the wall, or to live in the watchtower as poet-in-residence—but ultimately bunkering down in the hopes that the inevitable return to reason will arrive shortly. Wait out the storm, they say in their quiet, polite voices. Hillary is an inevitability. But if you let the great violent noise of the political hurricane drown out these quiet voices and instead squint upwards, tracing the length of that wall until it ends amidst rain and thunder, you might also catch a glimpse of other barbarians patrolling the perimeter, their hulking shapes marking out the border of the urban palace itself.

Because the truth is that the rise of global barbarity is matched in the traditional imperial fashion: the empire draws in warriors from closer hinterlands to defend against domestic threat and foreign invasion. When the choice seems to be, as always, communism or barbarism, the liberal chooses barbarism every time. The choice invariably takes the disguise of defending against greater barbarities to come, even while it forms their foundation. In the short term, cops can commute in from the whitening, Trump-voting exurb to patrol the financial district or quell uprisings across the inner ring suburban slums. In the long term, the bureaucrat tends to cultivate a militant tribalism that threatens dynastic stability.

Seen from such distance, that vast terra incognita called “Trump Country” tends to be understood less as a result of crisis than as a sort of widespread moral failure in which wrong ideas among poor whites have, in turn, generated the economic crisis in these areas through the election of anti-tax Republicans. The utter collapse of the industrial structure (and thus the actual tax base of such counties) is thereby elided. It also becomes possible to all-too-easily attribute things such as the election of Trump to a single demographic: that mythically homogeneous “white working class.” The existence of large swaths of non-white rural poverty (in the Dakotas, in the Mississippi River Delta, across the Southwest) is simply ignored, and the features of present-day rural white poverty (as elsewhere: persistently high unemployment, low incomes, prominent black and grey markets, increasing rates of incarceration, rising mortality, morbidity and drug addiction) are seen as moral failures precisely because liberal privilege politics falsely extrapolates individual characteristics from general statistical trends in the racially-unequal distribution of power.

In short: because whites generally wield disproportionate political, economic and cultural power, poor whites are seen as having no good excuse for being poor. The only explanation seems to be that they must have failed at some personal level to cash in their “privilege,” even if they are, for example, an unemployed youth taking care of opiate-addicted family members in McDowell County, West Virginia, where life expectancy falls somewhere between the average rates in Nepal (for men) and Nicaragua (for women). This is essentially the liberal equivalent of the die-hard conservative living in a house bought with a hefty inheritance, complaining about how “minorities” squander all that money the government supposedly gives them for free. But the “white working class” is a manufactured antagonist (or protagonist for some of the ascendant socialist groupings) defined by conservatives’ vague nostalgia for the brief postwar industrial compromise. As with all forms of nostalgia, the image misportrays the past in the name of an obscured present. The irony here is twofold: first, it lies in the fact that the only workers who comes close to experiencing the conditions nostalgically associated with this “white working class” in the postwar era are, in fact, urban workers in high-end services, information technology and a small number of (now highly mechanized) remnant Fordist manufacturing firms like Boeing—in short, one of the base demographics for liberalism itself. Second, there is irony in the fact that this handful of workers experiencing the conditions most similar to that of the historic “white working class” are precisely those most likely to demonize poor whites, who mostly do not vote, for catapulting Trump into the presidency. Instead, all evidence points to the fact that Trump was elected with a more diverse base of support than initially suspected, and higher-income whites composed a substantial portion of this base. Thus, the mirage of a “white working class” as the vanguard of Trumpism tends to obscure both class stratification within the white population and the actual conditions lived by those on the lower rungs of the white proletariat, historically derided as “white trash.”

The rise of new cultural practices in the midst of such pervasive crisis tends, for the liberal, to take on the same barbaric characteristics associated with this underclass. The rise of MMA is a case in point. When the UFC began, it was widely derided as a barbaric bloodsport, its white trash audience drawn from the most industrially obsolete and culturally backward parts of the country and its approach to combat stripped of any art or cultural integrity—the polar opposite, in a way, of the curious urbanite learning about “Eastern Culture” by practicing Tai Chi, Taekwondo or Japanese swordsmanship. In popular culture, the vision was appropriately apocalyptic: Any proper film set in a dystopian future invariably includes scenes of cage fighters spitting blood across the audience at the cyberpunk dive bar as the crowd cheers and strippers’ naked bodies writhe behind neon-lit smoke.

This image of white trash barbarity is somehow evoked despite the UFC’s international origins (the tournament originated among the Gracie family, patriarchs of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu) and diverse cast of fighters. The very first fight of UFC 1, in 1993, saw Dutch karateka and kickboxer Gerard Gordeau face off against the enormous Samoan Sumo wrestler Teila Tuli. Without any weightclasses, the fight was one of the most mismatched in UFC history, with Gordeau weighting in at around 200 pounds and Tuli at 415. Nonetheless, the match was over in less than thirty seconds, Gordeau landing a kick to the face that sent one of Tuli’s teeth hurling into the audience like a blood-tailed comet. As the tooth landed it struck a nerve in the crowd, the comet carrying some sort of maddening portent of the future. This was the early ‘90s, the years of Terminator 2 and Judge Dredd, when a smog-filled, bullet-riddled LA seemed to foreshadow something just over the horizon. In a mirror image of the dystopian dive bar, the cheers of the blood-spattered audience drowned out the judge’s decision handing Gordeau the fight. And it was doubtless the audience that gave the early championship its air of hillbilly barbarism, rather than its diverse cast of fighters.

UFC 1 – Gerard Gordeau vs Teila Tuli by robeu

Sometimes, the championship seemed to recruit directly from this audience. Two years later, UFC 5 was inaugurated with a now-notorious fight between John Hess and Andy Anderson. Anderson himself was one of the sport’s early fans, visible in the audience on the VHS recordings of the early tournaments before miraculously appearing in the ring with a clearly falsified record (86-0). Both fighters were the very image of the state of the white working class circa 1990: matching beer guts and crew cuts, Hess a “master” of his own fighting style, Scientific Aggressive Fighting Technology of America (SAFTA), and Anderson, a strip-mall martial artist wearing a tank-top emblazoned with the words “Kick Ass” who obtained his spot in the fight by supplying the event’s ring girls, employees at his “Totally Nude Steakhouse” in Gregg County, Texas. The match, if it can be called that, was like a dirty barfight between two cat-calling, casually racist construction workers. Both men hurled sloppy windmill punches with no concern for where they landed, swapping out wrestling takedowns for drunken football tackles and breaking the few rules that the early tournament operated by. Hess gouged Anderson’s eye (popping it out of socket and causing permanent damage), pulled his hair, bit off chunks of his hand and ended the fight with a series of soccer kicks to his opponent’s prostrate body. Hess himself was too injured to carry on in the tournament and only had one other fight in his MMA career—against a 19-year old Vitor Belfort, a true mixed martial artist (now widely considered one of the best to have ever competed) who defeated Hess within a matter of seconds. Though Anderson never fought again he did stay true to his public image, later joining the Aryan Brotherhood and being sentenced to thirty years in prison for money laundering and conspiracy to distribute methamphetamine.

Though often brutal, the treatment of these early fights as little more than a barbaric bloodsport is itself a good case study in the class hatred that sits behind the apparent compassion of liberalism. In the same way that the wealthy urbanite’s security depends on a disavowed reliance (in the form of the vast military, police and prison apparatus) on the very barbarians s/he derides, cultural scorn directed at gun-toting rednecks also contains an identical disavowal. The liberal’s hysterical op-eds about rural voting habits, the hipster’s hatred for the heteronormative façade of the Bible Belt, and the professor’s snide dismissal of those who believe in chemtrails and other assorted conspiracies—all use the old tropes associated with the white trash underclass in order to thinly veil a more widespread scorn of the lower classes in general. The barbarity of whiteness is the only politically-correct stand-in for the general barbarity of the proletariat. It’s not coincidental that poor whites seem to increasingly become the target of scorn for their wrong ideas about race, gender or science just as wealthy coastal elites continue to concentrate the shrinking pool of economic vitality more and more heavily into a handful of palatial urban complexes. Cultural scorn is simply the embroidery of this material theft. Liberal derision for the conservative outgrowths of poverty thus fuses with conservatives’ own scorn for the local underclass to form an integrated whole in which both factions of the rich, when combined, compose a totalizing hatred for the lower class in its entirety.

This hatred diffuses into popular ideology via critiques of culture. On the conservative side, this is primarily a critique of “the culture of poverty.” For the more liberal faction of the ruling class, the critique is that the poor are poor because they lack culture as such. In a widely-publicized award speech following the election of Donald Trump, the actress Meryl Streep described the apocalyptic cultural horizon foreboded by the election: “Hollywood is crawling with outsiders and foreigners, and if we kick them all out, you’ll have nothing to watch but football and mixed martial arts, which are not the arts.” In response, UFC president Dana White, alongside many fans and martial artists, took to the internet the attack Streep, Hillary Clinton and the liberal status quo that they represent. White’s own comments were a mixture of personal invective and the simple observation that the UFC and martial arts more broadly are defined by their diversity, attracting fighters from all over the world. At the same time, White himself had spoken at the Republican National Convention, drawing on martial metaphors to endorse Trump: “I’ve been in the fight business my whole life. I know fighters. Ladies and gentleman, Donald Trump is a fighter and I know he will fight for this country.”

For the establishment liberal, martial culture is an unrecognizable degeneration of “art” and a symbol of the dystopian future—its dystopian status marked not by mass unemployment, economic crisis and increasing precarity, but by the absence of the finer things. Streep’s speech was essentially a eulogy for the beautiful lie that liberals had enjoyed in the Obama years: the myth that, as long as we had surface-deep diversity and the continual cultural output of a “creative class,” all the brutalities of the presently existing world could be enjoyably ignored in the hopes that things were getting better. For the Trump supporter, meanwhile, the martial is itself a metaphor for political practice. The physically pathetic demeanor of a president as flaccid as Donald Trump is somehow transmuted into a strength capable of combating the decrepit liberal establishment on behalf of common people.

Weakness

The Boxer rebellion grew out of a long line of millenarian cults, but it was unique in its ability to fuse militia activities, martial arts, and state patronage in a way that at least momentarily seemed capable of rejuvenating, rather than overthrowing, the collapsing Qing administrative structure. In the lead-up to the rebellion, parts of Shandong had been occupied by foreigners (namely the Germans, responding to attacks on local missionaries) and the provincial government was in a state of perpetual fiscal crisis. In such conditions, many commoners had turned to banditry and, in response, local elites formed extensive militias to protect their patrons and property. Though they recruited from the underclass, the Boxers were not an egalitarian religious cult like that led by Hong Xiuquan in the Taiping Rebellion. Instead, they were inextricably linked to the skeletal remnants of the Qing state and local gentry. In the same way that the Patriot Movement tends to defend the interests of landholders and petty industrialists in the Western states even while ensconced in a working class aesthetic, the Boxers, though staffed by poor young men, sought to rejuvenate the Qing in the face of foreign threats, with the direct patronage of factions within the state itself.

But this patronage was not the only source of the movement’s relative popularity. The Boxers were able to ignite a more widespread anti-foreigner movement due to their emphasis on rebuilding strength in the face of growing national weakness. Whether local adherents may or may not have agreed with their political program was irrelevant. In fact, the Boxers had hardly any political program at all. They were a largely pre-political conservative upsurge, their ideology remarkably similar to the unsorted bargain bin of paleoconservatism and memetic occultism that unites the contemporary far right. The Boxers were unified only by physical shows of strength, a vague belief that they had inherited ancient, esoteric rituals, and the simple myth of an undefined national unity, encapsulated in their demand to “Support the Qing.” Their adherents were attracted primarily by the performance of strength itself—the simple idea that a force strong enough to give power to the powerless had finally come. With the defeat of the boxers at the hands of the eight-nation imperial army, this illusion was deflated. But the core desire remained.

Probably the most consistently wrong-headed understanding of the ascent of physical culture in eras of economic collapse is also one of the most common interpretations, particularly on the left. The roots of this critique come from the deeply conservative strains of Cold War academia that arose in the postwar West. Drawing from selective readings of the Frankfurt School, many of these writers and theorists—often affiliated with CIA front groups such as the Farfield Foundation, which was integral to the explosion of creative writing programs across the country—defined themselves by an opposition to “modernity,” embodied in the dual “totalitarianisms” of Fascist Europe and the Soviet Union. In this view, the modern reinvention of the human was defined by an obsession with hierarchy, domination, and both physical and industrial might. Fascists and the Communists alike had been obsessed with a New Man, represented invariably in statuary, strapped with muscles and operating heavy machinery: the perfect fusion of state, industry and society. The most complete version of this thesis was stated by Susan Sontag, who claimed that communism was simply “a variant, the most successful variant, of Fascism. Fascism with a human face.”

Sontag’s claim is particularly important, since her essay, “Fascinating Fascism,” has served as a sort of foundational blueprint for leftist critiques of physical culture. The essence of the argument has been repeated ad infinitum, often by those who seem to have no actual familiarity with the original—this is, of course, a common feature of anything that accords with a given era’s ideology, its basic logic reproduced by the ambient cultural conditions, independently of any direct lineage. Sontag’s essay focuses on a book of photography produced by Leni Riefenstahl, the preeminent artist of Nazi Germany, known for her spectacular visuals of human bodies engaged in strenuous physical work. Sontag’s basic conclusion is simply that this sort of focus on strength as such, is an inherently fascist activity. Similar conclusions have been most recently reproduced in an essay printed in the art-and-fashion magazine Refigural. Though the essay itself is not of any particular note, it is significant here, first, as a case study in the recapitulation of standard tropes, reformulated into a polemic against the rise of health goth and fascist-looking haircuts, and, second, for the fact that it was widely distributed within the world of vaguely communist artists, offering a more contemporary example of the general phenomenon.

What tends to unify this species of critique across its many local manifestations is the attempt to sever questions of culture and aesthetics from the material facts of class conflict as embodied in a given historical moment. The most remarkable thing about these sloppy polemics against things as laughable as wearing Adidas or cutting your hair too short is not the inelegance or sheer art-school stupidity of their arguments, but instead their delusional drive to ignore the world as it exists, pretending instead that “discourse,” “aesthetics” or one-summer fashion trends are closed-loop cultural circuits, thought birthing art and vice versa. In a way, this is a summary of the abysmal “cultural turn” in general—and the irony here is that the rise of physical culture is itself a sort of mass, popular response to this insulated shit-loop of art and academia that’s supposed to represent “resistance” in an era of forever wars and thirty-year economic decline.

We are told by Sontag, echoing Streep, that the roots of physical culture and its correlated aesthetic are easily identifiable: “To an unsophisticated public in Germany, the appeal of Nazi art may have been that it was simple, figurative, emotional not intellectual,” a type of art that offers common people “a relief from the demanding complexities of modernist art.” This is the sum of her explanation for how such a cultural movement rose to prominence, the diagnosis little more than a barely-veiled invective against the stupidity and unrestrained passion of the proletarian horde, incapable of understanding real art. Similarly, the recent essay from Refigural simply casts a broad net of vague associations in the classic thinkpiece fashion, here garnished with a bit of art-school loftiness. But throughout, the argument simply takes the rising prominence of physical culture and its aesthetic correlates as a priori fascist, a thesis “proven” through the simple fact that many on the far right seem to be drawn to guns and muscles and that frat boys also, in fact, like sportswear—big fucking surprise.

What neither work contains, however, is any rigorous approach to history. For Sontag, proletarian brutishness is enough. There is simply no reason for her to dig into the intricate history of German physical culture, rooted in the late 19th century and often deeply tied to early nationalisms and the rise of the worker’s movement. Nor is there any reason for her to trace the transfer of this particular strain of physical culture to the US via the migration of German workers and radicals into the American working class. There is no analysis of the role that physical fitness played in the social clubs of the early worker’s movement. Nor, remarkably, any mention of the ways that physical culture was directly mobilized against the rising Nazi threat, as seen in groups of communist streetfighters, or Imi Lichtenfeld and his gang of Jewish wrestlers and boxers defending their neighborhood in the midst of anti-semitic riots. This is because, for Sontag, the particular far-right adoption of physical culture within Nazism is symmetrical to the role it played within the broader workers’ movement from which it emerged. If communism is simply the “most successful variant” of fascism, there is simply no difference between the Nazi Olympics and a working class gym where people might learn the skills needed to fight strikebreakers at work or racist gangs on the street.

Thus severed from this history, such analyses play a purely ideological role. These critics find themselves in an historical moment when the flesh of the planet is being ground to pulp, when old emancipatory movements have been defeated in a century-long avalanche of blood, and when the poor today are increasingly living a life that seems to be composed of little more than curling into a fetal position while being constantly stomped under the boots of a million different species of police—and faced with this our brilliant Leftist declares “well, actually” your desire for strength is inherently fascist. The only time the liberal ever walks off the sidewalks and into the streets, after all, is to separate the fascist and the anarchist brawling through the labyrinth of stalled traffic, their intellect resounding with the mind-numbingly cultured revelation: “you’re just as bad as they are!”

Fascism in the Flesh

In both Germany and China, the rise of physical culture was a product of political fragmentation and economic immiseration. Emerging in relatively undeveloped, territorially fragmented nations nonetheless loosely linked by a degree of shared language and culture, it’s not surprising that the early movement took on features that were simultaneously nationalist and proletarian. The physical culture of the Boxer era in China was, in its vague nationalism and muddled politics, remarkably similar to the physical culture of Germany in the mid-19th century. So why does the latter seem to encapsulate the very core of fascism as physical spectacle, while the former never merits a mention?

The problem is a sort of fallacy of hindsight. Knowing the fascist conclusion of the early sequence of German nationalism, every element of culture (physical or otherwise) mobilized by the Nazis is, in retrospect, re-envisioned as fascism in its germinal form. This is despite the fact that fascism, by its very nature, grows through a co-optation of the most effective, popular features of pre-existing emancipatory movements, mobilizing them in a fanatical defense of the status quo, re-imagined as a struggle for national restoration or the return to a salvific natural order. In every instance, fascist movements steal their tactics and aesthetics from the left, mix in esoteric symbols and images drawn from a “lost” tradition, and then compete with that same left for influence among the broader working class. Their mobilization of physical culture in this way is, in essence, no different than their use of realist art or collective displays of strength. But knowing the result of this history, one is prone to misread fascism as a sort of cultural contagion, capable of infecting through mere contact with any one of its larval forms. Your hip haircut is not simply a haircut but instead a fascist parasite clasped to your skull, slowly transforming you into a Nazi. Weightlifting is a gateway drug, putting your life on a path that ends in an amphetamine-fueled blitzkrieg against the decadent French.

The reason that key features of Chinese physical culture aren’t perceived in the same way is, similarly, caused by hindsight. We don’t see Kung Fu as inherently fascist simply because the Boxers lost in a miserable fashion and the more developed Nationalist attempt to resurrect physical culture was defeated by the communists in both military and cultural fields of combat. The same was not true in neighboring Japan, where the Samurai tradition would long be tarnished by association with soldiers slaughtering unarmed civilians with katanas in places like Nanking. Japanese physical culture could only be recuperated under the oversight of the US military. This recuperation took the form of both a domestic revival—one of many attempts made to foster peacetime reinventions of local cultural practices, accompanied by generous economic aid and complete military occupation—and of the internationalization of Japanese techniques via American culture. The foreign soldiers occupying Japan began to learn native styles of armed and unarmed combat, bringing them into the Western cultural sphere upon their return and thereby providing the necessary groundwork for the first major revival of interest in martial arts within the US. Military hubs like Hawaii would be among the first locations to see a new series of inter-style challenge matches, resulting in the development of new loosely-combined “styles” such as Kajukenbo, prefiguring modern MMA.

The divergent historical outcomes of China, Japan and Germany signal that fascism is not contained in germinal form in its preceding cultural signifiers, but that these cultural practices are themselves highly contingent fields of class combat. Sontag and other critics are broadly correct when delineating fascism’s core philosophical obsession with strength for the sake of strength, the affirmation of pure life, the belief in a salvific natural order sorted through feats of spectacular violence, etc. This correct, incisive anatomy of the fascist philosophy is precisely why such critiques initially seem to provide a strong foundation for an understanding of fascism as such. But fascism is not solely a philosophical system, and purely aesthetic or theoretical approaches to it will tend to disguise their lack of substantial historical grounding with ever-more expansive psychological diagnosis—and in the end is anyone really that surprised to find out that the orderly Nazi aesthetic holds a barely-disguised eroticism, the performance of strength a hyper-sexualized fetish for domination, the stress on clean living accompanied by rampant drug use and illicit sex? But such conclusions are offered in an endless cascade, each bongrip epiphany of the amateur psychologist illuminating less than the last. In the end, we get no real sense of how or why these co-opted cultural features combined in this way to form this peculiarly fascist way of thinking.

But if we turn from psychology to history, the fact is that there was simply nothing guaranteeing that German physical culture ended in fascism. It was, after all, rooted in the exact same historical and cultural terrain that produced the communist movement as such—and this is doubtless why Sontag must equate the two so directly. Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, founder of the “Turner movement” composed of a network of gymnastics clubs (Turnvereine), was an early German nationalist whose philosophy was similar in character to that of the Boxer-era martial arts revivalists in China some hundred years later. He advocated a vague, semi-modern nationalism defined by its call to overthrow foreign domination (in Jahn’s case, the French invasion of Germany under Napoleon). His thought would later be adopted by the Nazis, where it was filtered through the work of secondary scholars who emphasized his loosely-defined nationalism and made a direct equation between the development of the physical body and the development of the Volk as such.

But Jahn’s own philosophy, though often romantic, nationalist and anti-foreign, was also substantially more ambiguous. He was considered a threat by the German state for his populist views, imprisoned in 1819 and exiled briefly in the late 1820s, his gymnastics clubs were often closed with the justification that they were organizing hubs for political radicals. And many of the first-and-second-generation Turnerites did in fact go on to participate in the revolution of 1848, rubbing shoulders with prominent early communists, including Marx and Engels. When the revolution was crushed, the most left-leaning of the Turnerites were exiled alongside the radicals. German physical culture was thereby introduced into America via the same migration routes that would flood US cities with politicized European manual laborers. This formed the basis for the early American worker’s movement, with its backbone of social clubs founded by immigrant communities producing radical literature in their native language (especially German and Yiddish) and providing space for basic community activities.[7]

Among these activities were gymnastics clubs, founded by the Turners, many of whom would go on to fight on the Union side in the Civil War and then take leading positions in the labor movement of the later 19th century. August Spies, a prominent anarchist best known as one of the martyrs executed following the Haymarket bombing, was also a member of Chicago’s Aurora Turnverein. Spies’ execution marked the height of radical activity among the Turners, as internal splits between more conservative, middle-class Turnerites and the socialist-leaning, working class wing of the movement slowly saw the conservatives gain ground as the original generation of Forty-Eighters died off.[8] But the experience of American Turnerism, as embodied by figures like Spies, proves that Jahn’s philosophy of physical culture could trend to the left just as easily as it would later be recuperated by the right.

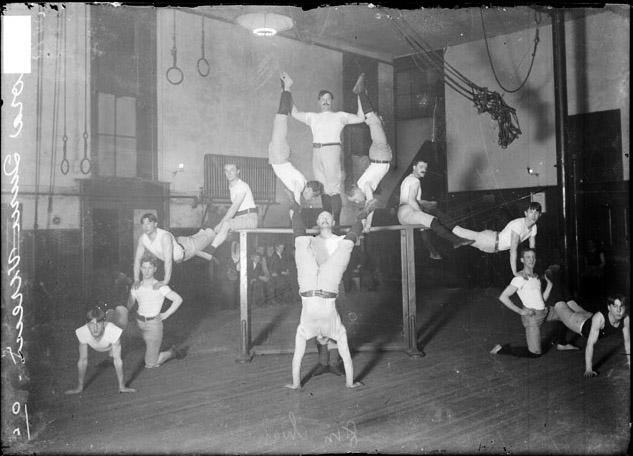

Members of the Aurora Turnverein, of which August Spies had been a member, photographed in 1906. SOURCE: Chicago History Museum

Kung Fu and Class War

The same fundamental contingency can be seen in the constant back-and-forth within Chinese physical culture following the Boxer rebellion. Efforts to revive and modernize the martial arts regained popularity both before and after May Fourth, diffusing widely within the early, left-leaning Nationalist movement (centered on Sun Yat-sen’s Tongmenghui, with membership drawn from the secret societies) and within the ill-defined anarchist movement. Politics in this period were amorphous, short-lived tendencies forming, evolving, fusing and becoming extinguished, their members distributed in the end to either the later Nationalist or Communist Parties. This early overlap existed as much in martial as intellectual circles, both of which only sorted into clear factions much later.[9] The rudiments of a fully nativist, fascistic physical culture can be seen in this period, embodied in the New Life Movement of the Nanjing decade, and similar in character to that which would take hold among the Japanese martial arts community. But, in competition with this trend was an equally powerful internationalist form of physical culture, originating among the anarchists and diffusing into the Communist Party that succeeded it.

The anarchist movement in China was strongest in cosmopolitan coastal cities, where it took a form largely copied from its French, Japanese and US counterparts. Student and labor exchange programs were key to its early formation, establishing direct contact between Chinese anarchists and well-known theorists and organizers within the global movement. Works by Bakunin and Kropotkin were widely translated and published in popular anarchist newspapers. Anarchist literature was so pervasive that even the early membership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) would have had far more direct familiarity with the anarchist classics than with the works of Marx or Lenin.

Meanwhile, both the early anarchist groups and the Tongmenghui had already absorbed a certain low level of martial focus from their affiliation with radical secret societies and their involvement in prominent assassinations during the last years of the Qing dynasty. Liu Shifu, a leading force in the anarcho-syndicalist circle in Guangzhou, had originally been a member of the Chinese Assassination Corps, inspired by similar groups in Russia (People’s Will) and Eastern Europe (Black Hand). Though assassinations by such groups arguably played a key role in bringing down the Qing, their insular activities were soon superseded by a series of mass uprisings that culminated in the Xinhai Revolution in 1911. Many leaders in the movement, Liu included, thus shifted their attention from isolated insurrectionary groupings to mass organizing. But the martial element of their organizing didn’t simply disappear.

The Guangzhou Circle of anarchists would found the first modern labor unions in China, modeled after the French syndicates.[10] However, as in Europe, Japan and the United States, labor organizations alone were not the extent of anarchist organizing. The group also ran newspapers, and previously secret meeting-spots for the anti-Qing societies became public centers for lectures, debates and other social events. Martial arts and gymnastics clubs would become a prominent feature of this early, urban phase of class conflict in China. Inherited martial traditions, in the form of gangs, religious sects and secret societies (often overlapping) would combine with attempts to “modernize” the martial arts and incorporate more elements of Western science and gymnastics (much of which was linked distantly to Turnerism through the influence of both radicals and more conservative groupings like the YMCA).

Throughout this process, the anarchist (and, later, communist) factions in the urban class warfare of the early 20th century were consistent advocates of an internationalist vision of both politics and culture. Liu was an avid speaker of Esperanto, and made sure that the Guangzhou labor movement had a steady supply of newly-translated writings and foreign lecturers. Exchange programs helped local radicals travel to France and Japan, where they worked with labor organizers and saw the wide array of services provided by the syndicalist or social democratic movements. When they returned, they attempted to combine what they’d seen with the variety of primitive revolutionary organizations inherited from the fall of the Qing.

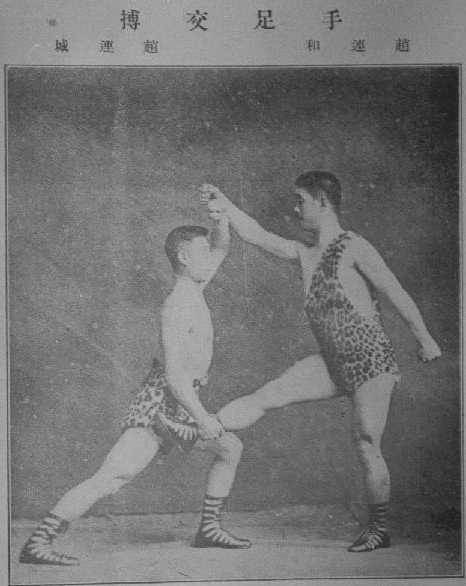

These same coastal cities also became the sites for the earliest modern martial arts schools, at first run largely through the reformist Jingwu Association, which introduced the model of sustaining itself through a paying membership and thus divorced the martial arts from their village-military, religious or secret society roots.[11] The association aimed to not only preserve and synthesize the martial arts, but also to clearly distinguish them from the superstitious and backward practices associated with the failed Boxer rebellion. They therefore advertised the practical aspects of combat and the positive effects of exercise on health rather than invoking esoteric rituals or the mythic histories of Buddhist warriors and Daoist immortals invented in the pulp literature of the era.[12] It was also one of the first organizations to publicly allow the participation of women, many of whom became prominent symbols of the new physical culture of the Republican period.

The Jingwu Association was a more moderate variant of the combative martial clubs that would soon form as the post-Xinhai political currents polarized into Nationalist and Communist factions, both challenged by local warlords. But the association’s basic vision retained the softer nationalism of the Tongmenghui, seeking to dispel the image of the Chinese as “sick men of East Asia,” and instead create a “new Chinese citizen,” who would be “proud, well-educated, physically fit, morally upright, and able to stand up to physical challenges from any source […]”[13] The organizations’ founding myth was that the patriarch of its martial arts program, Huo Yuanjia, had publicly defeated a European strongman stage fighter who claimed that he could defeat any Chinese man. But Huo died soon after the organization was founded, the myth having it that he was killed by an “evil Japanese doctor” who poisoned his food. Despite benefiting from the mystique of such stories, the association’s approach to the martial arts was highly rational. The Jingwu founders sought to incorporate “modern (and Western) ideas of sports science, medicine and nutrition into Chinese martial arts” and to eliminate the many superstitious and often unhealthy practices that the various arts had accumulated.[14]

The Jingwu also represented the first major attempt to combine the various martial systems that had evolved via local village-military practices, often segmented by ethnicity and local dialect, into a coherent system of “Chinese” martial arts. In reality, the association was ultimately only able to draw from the styles of (more ethnically homogenous) north-central China, never fully incorporating Mongolian wrestling or any of the diverse southern Chinese styles.[15] With its main organization located in Shanghai, it was also surrounded by practitioners of western boxing and wrestling, as well as Japanese martial arts, and likely drew from some of these practices in its attempt to create an “authentic” Chinese style.[16] This foreign influence was clearest in the association’s regular weightlifting program, which emulated the Western strongman tradition to the point that its muscle-bound members even posed for photos wearing wrestling boots and bizarre 19th-century leopard-print singlets.[17]

In the economic turmoil of the 1920s, the major funding sources for the association dried up and it closed its doors. But that wasn’t the end of the martial revival. Over the course of this tumultuous decade, physical culture would take on a more explicitly political role. In the Pearl River Delta cities of Foshan and Guangzhou, older family-style martial arts were converted into public schools and often recruited widely from the cities’ growing class of migrant workers. Martial clubs were particularly appealing to poorer laborers who couldn’t join clan associations or guilds. This was clearest in the experience of the Hung Sing school of Choy Li Fut, which began to expand in Foshan at the turn of the century, recruiting a large number of adherents from the city’s growing working class who were excluded from the “masters’ guilds” serving skilled workers.[18] The Hung Sing therefore filled the same gap as Liu’s anarcho-syndicalist unions in neighboring Guangzhou and, by the 1920s, the school had begun “to play an undeniably important role in the evolution of the local labor movement and Communist Party in Foshan.”[19]

But martial clubs were not only utilized by the left. The soft nationalism of the Jingwu Association—with a middle-to-upper class membership, helmed and funded primarily by three businessmen running a trading company[20]—ultimately gave way to both more exclusionary nationalist interpretations of the martial arts and to the mobilization of martial clubs for strikebreaking, factory and bank security, and politically-motivated street fighting. In Foshan, this culminated in battles between the Hung Sing Choy Li Fut school and the Zhong Yi Martial Arts Athletic Association (Zhong Yi Guang), which taught Hung Gar and Wing Chun. Both of these were family styles initially developed and transmitted within the clans of wealthy landowners, in contrast to Choy Li Fut, which had become a relatively eclectic style shaped by its use in earlier anti-Qing rebellions.

By the 1920s, the affiliation of the Hung Sing school with the Communists was formalized, with two of the four members of the CCP’s Foshan task force (aimed at creating an active Communist cell in the city) being drawn from the organization. Meanwhile,

The Yi schools aligned themselves with local businesses, “yellow” trade unions, and the rightwing of the provincial GMD [Nationalist] leadership. They clashed repeatedly with the Hung Sing Association over the various strikes and pickets promoted by the leftist organization. It would appear that the Yi schools were used as something like strikebreakers throughout the volatile decade.[21]

Whereas the Hung Sing was larger (with around 3,000 members) and primarily staffed by less skilled workers, the Zhong Yi was smaller (most likely around 1,000), more exclusive and more diverse, including “ordinary workers, businessmen, military personal [sic], local politicians and merchants.”[22] But this “diversity” was clearly an alliance between far right forces and a subset of conservative workers tasked with suppressing the volatility of the Pearl River Delta’s early working class

This large-scale revival and politicization of physical culture ultimately declined through simultaneous defeat and ossification. During the ascent of the Nationalists in the 1930s, an attempt was made to reconfigure the original aims of the Jingwu association under the banner of Guoshu (National Arts). As Guoshu, the martial arts were re-envisioned in the fashion of far-right physical culture in places like Germany and Japan. The Guoshu program attempted “to create a national, standardized martial arts program,” while also emphasizing the role of martial practice in the transmission of “traditional” Chinese culture, much of which had been only recently invented.[23] The Guoshu experiment suffered from the fact that the Chinese martial tradition didn’t contain the same intensely hierarchical, militaristic dimensions of its Japanese counterpart, and attempts to reform it in this direction were cut short by the outbreak of Civil War and the ultimate defeat of the Nationalists.

On the other hand, the martial arts tended to ossify under the CCP after its defeat in the cities (following the 1927 Shanghai Massacre) and shift to the countryside. Though the CCP continued to recruit martial artists and to deploy them in rural organizing, the rural shift brought with it an increasing militarization of the revolutionary project as a whole. The internationalism of the early communist and anarchist movement was increasingly replaced by a rural populism with a nationalist character and the expansive cultural and social programs of the early years were sacrificed in the name of military efficiency. Close quarters urban combat gave way to rural guerrilla warfare, making hand-to-hand methods largely irrelevant. Military training slowly replaced the more diverse physical regimens of the martial arts.

After the war, martial arts groups were treated with suspicion, the new state well aware of their ability to organize rebellions (especially dangerous in South China, the last area won from the Nationalists, still adjacent to colonial Hong Kong and Nationalist-controlled Taiwan). Though allowed a marginal existence, there was no true attempt to return to and modernize the martial side of physical culture. Instead, the government initiated the Wushu program in the place of the Nationalists’ failed Guoshu. Wushu (simply translated as Martial Arts) stripped the practices of their actual combative applications, transforming them into set forms, adding gymnastic aspects and creating a competition system based not on sparring but instead on formal features. Rather than a system of combat, modern Wushu is more of a “physically demanding type of folk dance or floor gymnastics with movements derived from traditional Chinese martial arts systems.”[24] Physical culture thus ossified throughout the socialist era, and has only more recently been revived in China, as Sanda/Sanshou (a kickboxing sport with rules similar to Muay Thai) emerged from its military roots to gain a mass audience and MMA begins to grow in popularity.

Sapateiro

Though many cultural practices that arise in a period of intense warfare, political fragmentation and economic collapse will initially tend to take on features of national salvation or preservation, these are clearly not the sum of the practice. Culture is malleable, after all, and like anything else it becomes one terrain for continual class conflict. Physical culture is therefore internally divided, leaning simultaneously to the left and right, and it is particularly indeterminate in the early years of its ascent. If it seems at the moment that the field is falling to the far-right, we should conclude not that the field itself is fascist. Nor, however, is it neutral. It is a terrain, with its own contours.

Sometimes this conflict takes the form of a combative, apple-pie American fascism. Beer-bellied, slow-punching dads guzzle supplements they saw advertised on the Joe Rogan Experience, get a Punisher bumper sticker and dream vaguely of a world where they could be men again. If you look into their eyes you will notice that they are watery, quivering pools of jelly with a glint buried somewhere deep down like a fire starved of oxygen. Their younger counterparts, on the other hand, attempt to balance actual martial skill with the perfect cultivation of show muscles for their invariably droll Tinder profiles. They almost always have the fanatic eyes of the tweaker, like they’ve seen things that can’t be unseen. Their physique is an encapsulation of their politics: the cancerous circle of muscular hypertrophy at the expense of functional strength—that old battle between the bodybuilder and the strength athlete. It’s a ritual that peaks quickly, bequeathing its practitioners with heavy, oxygen-hungry show muscles and a scarcity of martial technique. The crisis of capital embodied.

Alongside it all, of course, is an ever-accumulating population of sideline scumbags. These are the people that run the alt-right meme pages or huddle with their KEK flags behind the skinheads at the anti-antifa rally. They glory in calling out the weakness of the left and proclaiming their own expansive superiority. They lock their doors when they’re driving through the black neighborhoods, but, unlike their grandparents, they do it “ironically.” And actually they lock their doors in the poor white neighborhoods too. They are from the exurbs. Conservatism is the new counterculture, they say, vaping in their mom’s house. Really they just want the doors to be locked all the time. They just want to stay in the car, okay?

But class conflict operates in more subtle ways. Elsewhere, we’ve detailed the mobilization of Crossfit on behalf of the class interests of urban professionals. And the Crossfit theory of physical culture seems to provide evidence of particularly fascist features climbing up the class hierarchy, providing urban elites their own peculiar form of “primal” performance:

[…] Crossfit harnesses a nostalgia for a simpler past, and combines it with the romanticization of the natural in order to craft a comprehensible view of the present that embraces precarity by being prepared for everything. This is not simply a pre-lapsarian fantasy, though. The idyllic and savage “primal” is coupled with modern science in an attempt to recreate a born-again human that specializes in the unspecialized. As lean management forces all employees to be flexible in their working hours and expertise, Crossfit demands the same from their consumers. Crossfit is the figurative and literal lean production of the body.

This “leaning” of physical culture, taken up by the lowest rungs of the upper class, is where the greatest threat lies, because it poses the possibility of a future union between the fascist triad: the organic tweaker-fascism of the surplus population; the frat boys, exurban introverts and other princelings of capital; and the urban professional and executive classes that the former currently despise.

The first two have already begun a slow, miserable and incomplete fusion, starved of resources and lacking any mass character, the result being a condition of “fascists without fascism.” But with increasing instability, the threat posed by society’s dispossessed increases—and in reality the urban liberal (white or otherwise) is just as troubled by the riots that spawned Black Lives Matter as is the exurban conservative, a fact clearly visible when the entire political apparatus of black Democrats mobilized to extinguish the Baltimore riots. The soft-handed liberal will gladly appease the barbarians until the court itself falls. The lean liberal, on the other hand, will ultimately join the fascists, discovering a certain zest in the sheer “primal” power of so many bodies being accelerated at once. The Futurist and the urban decadent were as much a part of historical Fascism as the street-brawling worker, after all.

But, again, class combat doesn’t simply move in one direction. Once political polarization has reached a certain intensity the Hung Sing might engage in massive street battles against the Zhong Yi, but prior to this, challenges operate in a more subtle way. To take one example: In the midcentury martial arts scene in Brazil, the elite Jiu-Jitsu schools of the Gracie family, located in the wealthier urban districts of Rio de Janeiro, were constantly challenged by the poorer Luta Livre fighters as well as renegade Jiu-Jitsu dojos located in the suburban slums. All of these challenges took on a deep racial and class character, the contours of which can still be felt in modern MMA. But the roots of the divide within Jiu-Jitsu itself go back to the art’s introduction to Brazil in the 1910s.

Mitsuyo Maeda was the Japanese judoka most integral to the formation of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, best known as the teacher of Carlos Gracie, older brother of Helio and first of the Gracie lineage to learn the art. Carlos and Helio came from a wealthier family with extensive business interests and their initial introduction to the art came from the fact that their father was an investor in a major circus company, which contracted Maeda to perform. When they began teaching “Gracie Jiu-Jitsu” some years later, they predominantly marketed to middle-and-upper-class professionals, often leaving a subset of “secret” techniques to those within their immediate family.

But Carlos Gracie was not Maeda’s only Brazilian student. At around the same time that Carlos began studying under Maeda, Luis França had already been Maeda’s student for almost a year. While Carlos would teach his younger brother Helio the art, together founding the lineage that would later be thought of as synonymous with Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, França went on to teach Oswaldo Fadda, a poor man from Rio’s favelas. Fadda then began teaching Jiu-Jitsu to those in the slums through low-cost or free classes in public places. Without much money for promotion, he took out ads in the obituaries. The practice made him an outcast within the country’s budding Jiu-Jitsu scene, and this rivalry came to fruition in the form of an infamous 1951 challenge tournament between Fadda’s students and the Gracie school.

Both the Gracies and Fadda had themselves selectively developed and reinvented the art they had learned from Maeda. But while the Gracies (at the time) kept a subset of “secret” techniques within the family, Fadda taught openly and embraced a wider range. In the end, the tournament was decided by this range. Fadda’s team won by a landslide, taking nineteen of the twenty matches, according to most accounts.[25] The vast majority were won by leglocks, which were derided by the Gracies as “beneath” them—a “suburban” technique associated with the poorer, darker-skinned students of the favela schools. Whenever a match was won in this manner, the wealthier Gracie students would yell sapateiro (cobbler) at Fadda’s largely working-class students, an insult that hardly tried to veil its class and racial implications. To this day, prohibitions against “knee-reaping” in the official (Gracie-founded) IBJJF ruleset for sport Jiu-Jitsu are rumored to originate from this mid-century challenge, in which urban liberals fell one by one to leg-locking slum-dwellers.[26]

Strength

Today is again an era of barbarity. Screens flicker above drunken crowds. Blood is sprinkled across the Octagon like gently falling rain. And in China the same old questions of class, crisis and tradition have returned as they have everywhere else. The story is an old one, then, told through a challenge match: this time not between foreigners and native stylists, but between a self-taught Chinese MMA fighter named Xu Xiaodong and Wei Lei, a Tai Chi “master.” The result is predictable. Xu’s technique is poor, apparently learned in part from watching MMA matches online. He overshoots his target, exploding forward in a way that would lead to a rapid takedown or knockout against even a middling fighter. His punches lie somewhere between proper hooks and drunken haymakers. But despite all this, he’s able to pummel Wei into submission in less than fifteen seconds.

In the end, none of Xu’s shortcomings matter against Wei, who simply cannot fight. The Tai Chi “master” practices a style of Tai Chi (of his own invention, but descended from the broader Yang school) that long ago amputated any combat application. More importantly, he’s best known not for his martial arts prowess, but for his supposed magical abilities. His claim to fame was a feature on a CCTV documentary, in which he made a bird unable to leave his hand by using his “chi” to create a force field around it. Xu called him out as a fraud, apparently told by a producer of the show that the entire scene had been staged, the bird duct-taped to Wei’s palm. Wei himself, it was later discovered, had been a masseur before becoming a kung fu “master.” The polemics exchanged in cyberspace eventually evolved into the challenge match in Chengdu, which rapidly went viral.

In many ways, Xu’s attack on the corrupted “traditional” arts mirrors the early ascent of MMA in the US and elsewhere, based on bloody challenge matches undergirded by deeper class divides. Xu was driven not so much by a hatred of “tradition” as by a drive to violently root out the decadence and corruption of China’s new class structure. Wei Lei was a ready embodiment of that corruption within physical culture—and it’s not hard to imagine him as a stand-in for any number of corrupt businessmen or government officials. In fact, within a week of the video going viral, both the Chinese Boxing Association and the state-run Wushu Association issued condemnations of the fight, hinting that it might be illegal, and a prominent Guangdong billionaire was offering two million dollars to anyone who could beat Xu. Faced with such intense opposition from the rich and powerful, Xu himself has since recanted and gone into hiding, fearing potential reprisals. It appears that future challenge matches will not be allowed to go forward, or at least risk serious repression.[27]

Though embedded in a different cultural context, Xu’s one-man anti-corruption campaign has struck a chord with the global MMA community. Xu himself stated his goal simply: “[I] crack down on fake things, because they are fake. Fake things must be eliminated. No question.” And the sentiment resonates with the rising tide of populist politics, based less on any analysis of the global economy or consciousness of class than by a straightforward recognition that increasing inequality, driven by the “fake” bubble industries in finance and infotech, has created two very different worlds—one centered on the “creative” upsurge of wealthy coastal cities and the other on the vast, decaying global hinterland, defined by unemployment, rampant disease, drug use and low-wage work in black and grey markets. Xu, then, is the very image of that “barbarian” upheld by the far right: a warrior figure capable of pulling the soft-handed Tai Chi “master”—representative of every urban creative, “crony” capitalist financier, and government official—out of the liberal bubble and onto the mats. Wei’s ten second pummeling can therefore be understood as an act of populist iconoclasm, the warrior crushing the many illusions that found the liberal’s false sense of progress within a stagnating economy: urbanist revival, hi-tech industries and vaguely progressive technocracy all built on falsehoods as straightforward as a bird duct-taped to the palm of a masseur-turned-kung-fu-master.

Faced with such conditions, it’s too easy to observe the far right’s ascent and simply lose heart at the seeming inevitability of it. Certainly, if one subscribes to a theory of fascism-by-cultural-contagion it might appear as if we stand on the precipice of a coming pandemic, the encroaching disease visible in the diffusion of sportswear and close-cropped haircuts throughout the populace. A truly dystopian image for the granola Leftist. But even if the tide seems to be sloshing rightward, the Boxer rebellion and its aftermath should remind us that history has a longer arc. Despite any number of thinkpieces attempting to equate Trump’s America with late-Weimar Germany or Italy in the 1920s, the fact is that both of the European cases were ones in which Fascism arose out of the corpse of a widespread, well-developed leftwing movement that had failed in its many goals. The US is in no such position today. Instead, in almost every respect, the present situation more resembles that of late-Qing China, in which no leftwing politics had been able to cohere within the body of the decaying hegemon, and instead a superstitious, vaguely populist right rose to power in its absence. But its rise was premature. The historical sequence was therefore reversed: the left itself built strength out of the failure of the populist right’s attempt to seize power. Despite its ultimate militarization via the civil war and its subsequent descent into the management of a developmental regime, the Chinese communist movement shows that the far-right fusion of populism and physical culture can, in fact, be challenged.