With the launching of new material on this website, we are also archiving some articles that the handful of ultras involved in this project have written elsewhere. This is one of those archived pieces, originally published in another location. Note that some of the material below is slightly out-of-date. See, especially, the article Spontaneity, Mediation, Rupture in Endnotes 3 for a more recent take on similar topics.

Jodi Dean recently posted some annotations to Leon de Mattis’ article “What is Communisation?” from the first volume of SIC. For a while now Dean has had a limited engagement with communization theory—and we have many points of disagreement with both her method (using outdated, weak or non-representative articles) and many of her conclusions. But it would be equally disingenuous to provide a full critique of Dean’s position when she hasn’t produced any systematic criticism, aside from a few blog posts. Instead, we wanted to clarify a particular point of confusion that Dean (and many others) seem to regularly confront in communization theory.

The de Mattis article is one of the more poorly written and highly abbreviated articles, loose in lexicon, that are too often taken as indicative of communization’s main arguments—often because they pose themselves in those terms while, obviously, utilizing the kind of oversimplification expected in any “intro to” a given subject. Still, de Mattis draws out many of the central themes of the current and Dean touches on most of them in her annotations.

One, however, seems to be a consistent topic of confusion:

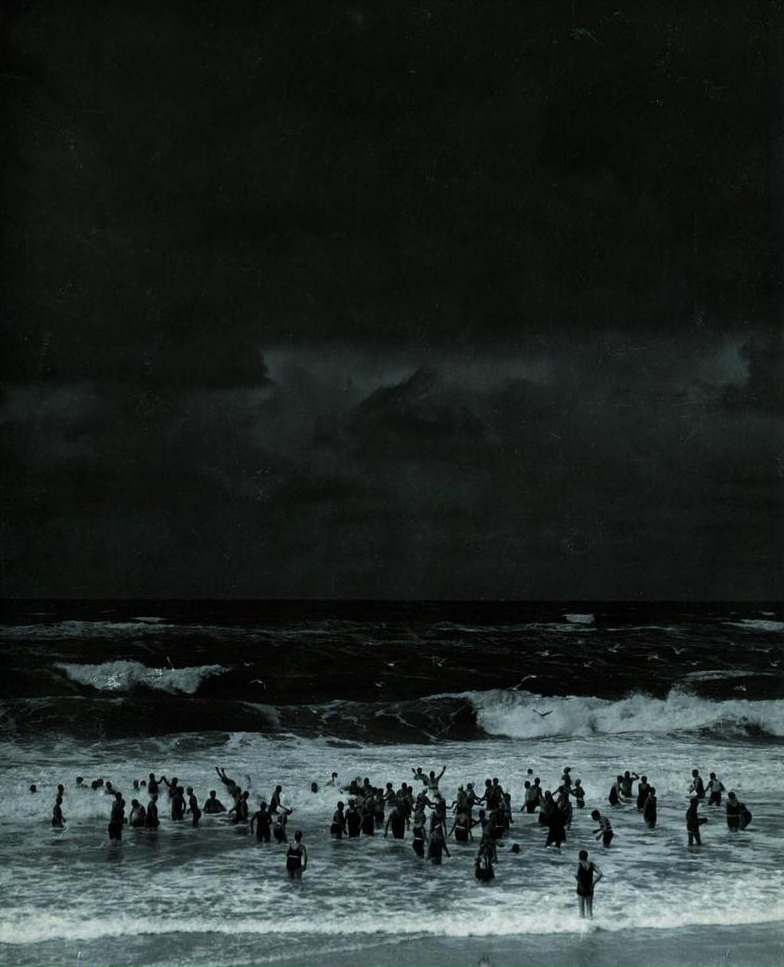

[money, the state, value, classes] are supposed to disappear in a moment, the moment of communisation. It sounds to me like the moment of a disaster, when people pull together in their immediate need […] The depiction of communism as a moment is unconvincing — it’s like another version of the idea that politics is momentary and fragile. Communism becomes an exception, the glimpse of the Real in capitalism […] Communism is the result of a massive and generalized social practice, this practice is communisation. I find this confusing: earlier he said that communisation was a moment […]

Dean hones in on the portrayal of communization as a “moment” and seems to find inconsistencies in de Mattis’ use of the “moment” as characteristic of communization—the author appearing to oscillate between portrayals of communization as the process of social practice (in/through struggle) and communization as a simple “moment” of spontaneous abolition.

To give some background to the issue (in order to speak of communization more generally), we’ll draw out a few quotes from other communization groups/theorists. First let’s look at one of Gilles Dauvé’s more frequently cited “intro to” articles. This is from the “Transition” section from the English-language version of the article, “Communisation:”

We would have nothing to object to the concept of transition if it simply stated the obvious: communism will not be achieved in a flash. Yet the concept implies a lot more, and something totally different: not simply a transitory moment, but a full-fledged transitory society […]It is obvious that such a deep and all-encompassing transformation as communism will span decades, perhaps several generations before it takes over the world. Until then, it will be straddling two eras, and remain vulnerable to internal decay and/or destruction from outside, all the more so as various countries and continents will not be developing new relationships at the same pace. Some areas may lag behind for a long time. Others may go through temporary chaos. But the main point is that the communising process has to start as soon as possible. The closer to Day One the transformation begins and the deeper it goes from the beginning, the greater the likelihood of its success.

So there will a “transition” in the sense that communism will not be achieved overnight. But there will not be a “transition period” in what has become the traditional Marxist sense: a period that is no longer capitalist but not yet communist, a period in which the working class would still work, but not for profit or for the boss any more, only for themselves: they would go on developing the “productive forces” (factories, consumer goods, etc.) before being able to enjoy the then fully-matured fruit of industrialization. This is not the programme of a communist revolution. It was not in the past and it is not now. There is no need to go on developing industry, especially industry as it is now. And we are not stating this because of the ecology movement and the anti-industry trend in the radical milieu. As someone said forty years ago, half of the factories will have to be closed.

And from a piece authored by the entire Théorie Communiste group, “Communization in the Present Tense,” published in Communization and its Discontents:

From the moment in which proletarians dismantle the laws of commodity relations, there is no turning back. The deepening and extension of this social process gives flesh and blood to new relations, and enables the integration of more and more non-proletarians to the communizing class which is simultaneously in the process of constituting and dissolving itself […] The dictatorship of the social movement of communization is the process of the integration of humanity into the proletariat which is in the process of disappearing.

[…]

The essential question which we will have to solve is to understand how we extend communism, before it is suffocated in the pincers of the commodity; how we integrate agriculture so as not to have to exchange with farmers; how we do away with the exchange-based relations of our adversary to impose on him the logic of the communization of relations and the seizure of goods; how we dissolve the block of fear through the revolution.

[…]

Communist measures must be distinguished from communism: they are not embryos of communism, but rather they are its production. This is not a period of transition, it is the revolution: communization is only the communist production of communism. The struggle against capital is what differentiates communist measures from communism. (pp. 56-58)

Finally, from Endnotes’ “What are we to do?,” also published in Communization and its Discontents:

If communization signals a certain immediacy in how the revolution happens, for us this does not take the form of a practical prescription; ‘communization’ does not imply some injunction to start marking the revolution right away, or on an individual basis. What is most at stake, rather, is the question of what the revolution is; ‘communization’ is the name of an answer to this question.

[…]

Communization is typically opposed to a traditional notion of the transitional period which was always to take place after the revolution, when the proletariat would be able to realize communism, having already taken hold of production and/ or the state. Setting out on the basis of the continued existence of the working class, the transitional period places the real revolution on a receding horizon, meanwhile perpetuating that which it is supposed to overcome.

[…]

Communization is a movement at the level of the totality, through which that totality is abolished […] The determination of an individual act as ‘communizing’ flows only from the overall movement of which it is part, not from the act itself, and it would therefore be wrong to think of the revolution in terms of the sum of already-communizing acts, as if all that was needed was a certain accumulation of such acts to a critical point. (pp. 26-28)

Each of these examples seem to contain the same tension between “movement” and “moment”—though, with this perspective, it’s also clear to see that “moment” seems far less emphasized. Nonetheless, all are very clear in the opposition to a “transition,” which would act as a “pause” or a “period,” where the working class sits on a Purgatorial plateau still founded in capitalism yet well below the starry-skies of communism.

So what does “the moment of communization” actually imply? Dean seems to hint that it might be an argument for an immediate leap (of the variety often associated with alternativist anarchism) directly (“overnight”) into communism. This assumption is one that is frequently repeated by critics of communization, particularly those coming from more orthodox socialist backgrounds. This is because it is rooted in century-old smear campaigns against anarchism, councilism and the “ultra-left” in general that constructed spontaneist straw-men to burn in the place of actual engagement. These straw-men were subsequently inducted into the dogmas of these orthodox trends and remain preserved there to this day, like mosquitoes trapped in amber—a handful of socialist microsectitians spending their lives trying to suck out the last few strands of DNA in the hopes that they might be able to resurrect some antediluvian Party, presumably to put on an island for tourists to come look at.

The problem with this position is, of course, that no one espouses it. Even authentic, miserable specimens of the variety alternativist more often than not understand their actions as a simple subtraction (“back to the land,” “dropping out,”), rather than an immediate prefiguration of communism. Outside of a few messianics and high-school anarchists, this position does not exist.

So what are the communasiteurs actually saying? Why speak of “the moment,” when a literal point-in-time would be so demonstrably absurd? If all one means is “movement,” why not simply give a libertarian model of the “transition?”

Put simply: communism names both the end goal and the movement toward that end goal, and this movement is characterized by a short-circuiting of the present and the future tense. Communization is the name for communist struggle which is simultaneously immediate (in-process) and the trajectory of the process itself. Communism acts with a virtual retroactivity—posited as a future ends it projects itself back on the real movement of people, forcing those engaged in struggle to constantly contrast their own actions with, on the one hand, the negation of capitalism and, on the other, the production of communism. Normal finitude breaks down and existing mediations become obsolete.

This is very much what Badiou has in mind when he frames struggle in terms of the Communist “Idea,” which contains just such virtuality and retroactivity. As Nathan Brown explains:

Communization, then, can be the Idea of some Subject—the manner in which historical determination is thought, or conceived, in the present cycle of struggle. And this idea can orient the daily engagement of the we, within a large historical movement with its deep tendencies, its restructurings, its necessities. Indeed: what else could be the practical pertinence of the theoretical usage of this term?

The thesis of communization, however, is neither normative nor prescriptive: this is precisely its dialectical power to formulate the double valence of historical determination as both process and subject. And we have to register the different problem of organization that the communization thesis imposes.

Ultimately, though, the seeming logical contradiction between moment and movement is not actually inconsistent, but speaks instead to the productive tension at the heart of communism: the tension between moment and movement and between movement and ends.

The problem with the “transition period” is, then, not the problem of transition (as Dauvé makes clear), but the problem of the “pause” as opposed to the continued movement, the “plateau” versus the upward “path” (to use de Mattis’ quasi-Maoist language). Similarly, the problem of counter-revolution sitting within revolution begins when the supposedly “revolutionary” fraction (be it a party, a syndicalist union, a Blanquist leadership or people in general) begins to pose itself as the “party of order,” opposing civil stability and consistent economic production to general dissolution of the present world, “anarchy” or chaos. Contemporary theories of communization are most similar, historically, to those of the factions in previous struggles who fought to take the risk (even if openly chaotic) and push without pause in constant revolution inward (socially) and outward (geographically), even when this meant renewed civil war. This doesn’t mean that the real movement of communization cannot be at all tempered or variable. The movement need not be at a single, set speed—it simply needs to be real movement with actual communist measures taken, rather than the building of an entire stable social(ist) system on the basis of capitalist categories (even if that system goes, in some limited way, beyond capitalism).

— NPC